If precarious employment is the new normal, how come we’re not talking about it?

According to the Toronto Star,1 “Precarious work is the new norm.” The same article reports on research findings from a 2013 study2 by McMaster University/United Way/PEPSO that looks at precarious employment in the Toronto region. This study found that less than half of all jobs in the Toronto region are permanent, secure full-time jobs, and outlined the devastating personal, health and community impacts of precarious employment. Furthermore, the study showed that this trend is affecting more people than one might expect – not just the working poor and it spans all sectors of the economy.

Precarious work is the new norm, study finds.

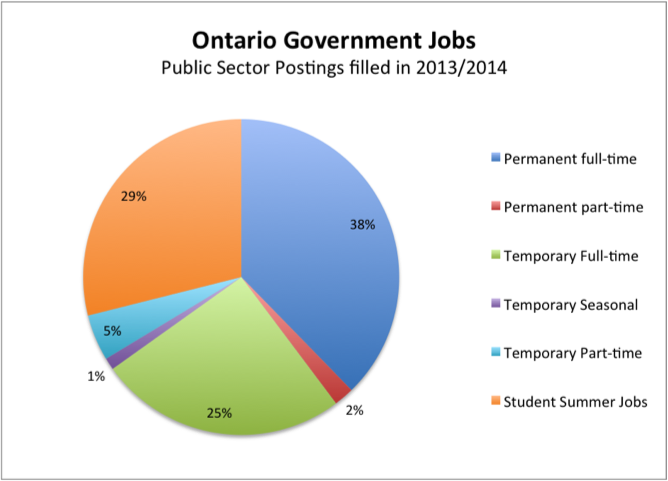

Ontario is having a lively debate on precarious employment. Unions such as CUPE 79 are mounting a “Good Jobs Campaign,” calling on the City of Toronto to end precarious work (close to half of unionized, municipal workers are in precarious employment not including agencies like the Police or the Toronto Transit Commission). Investigative reports are documenting just how prevalent precarious work is even inside the provincial government. Toronto Star reporter Sara Mojtehzadeh3 reports that most of the Ontario government’s own job postings filled in 2013-2014 were temporary positions.

Source: Toronto Star

The Ontario government is in the process of reviewing the province’s employment and labour laws, which like BC’s were created when full-time, secure employment was the norm, because it recognizes that current legislation is out-dated and offers very limited protection for precarious and vulnerable workers. In BC, the Law Institute of BC is reviewing employment standards, however, the review does not appear to be comprehensive nor to be engaging the public in a significant way.4

Given all the above, one seriously wonders why all is “quiet on the western front.” The public debate in BC on precarious employment appears to be close to non-existent. The odd newspaper5 article that mentions precarious employment in BC seems to look at precarious employment primarily as a problem impacting temporary foreign workers or the millennial generation, linking it to other worrisome trends such as rising student debt and housing unaffordability for young families in Metro Vancouver.

Here in BC, we need to talk about the shift to precarious work more broadly. As an independent researcher interested in investigating precarious employment, I’ve found out that my questions are intrinsically linked to other questions:

- Why is the BC government not taking a lead on this issue and actively working to understand6 and address this worrisome labour market shift?

- Why is it so difficult to get data that shows the true picture of the prevalence of precarious employment?

The public debate in BC on precarious employment appears to be close to non-existent.

We don’t have good data to assess and monitor the prevalence of precarious employment in BC, and this isn’t helped by the fact that there isn’t a commonly shared definition of precarious employment. Statistics Canada uses the narrowest definition possible, which does not show the whole picture. For example, the Labour Force Survey has collected data on the number of Canadians reporting their employment as seasonal, temporary or casual since 1997.7 However, the survey does not include questions about other aspects of precarious work such as access to sick days or extended health benefits. Nor does it outline the number of people who have ended up becoming self-employed (with no employees) to fit the new labour market reality of disappearing secure full-time positions and increasing contract work.8 Statistics Canada does not report regularly on post-secondary graduates who are unable to find secure full-time employment in their field of study.

A recent Freedom of Information request by my colleague Keith Reynolds reveals that precarious employment is not a concern for the BC government.

This seems short-sighted. Instead, the BC government could play a leadership role working with other provinces and the federal government to better understand and address this worrisome shift in the job market. This should involve working with Statistics Canada to add more questions about job quality to the Labour Force Survey and to develop a broader definition of precarious employment in Canada.

As it stands, both labour market regulations and our social safety net are based on the standard employment relationship as the norm (full-time work, secure employment, access to dental and extended health benefits, sick and holiday pay and pensions). A large number of workers in BC are no longer in standard employment relationships, which means they no longer have access to dental care, prescription drug coverage, sick pay, holiday pay or pensions though their employer and may not have access to employment insurance if they lose their jobs.

Precarious work is reshaping the world of work with serious negative consequences for individuals, families and communities. BC is ignoring this worrisome trend at our peril.

(I would like to thank Keith Reynolds and Iglika Ivanova for their support and for sharing ideas, research & their insights.)

Notes

[1] Precarious work is now the new norm, United Way report says

[3] Public sector workers feel sting of precarious work, study shows

[4] Underpaid & overworked? Help change BC’s labour laws.

[5] Staying in Vancouver stressful for millennials

[6] It is worthwhile noting that the lead research coming out of Ontario demonstrating how prevalent precarious employment in Ontario is has been academic/original research that wasn’t conducted by government. Investigative reporting (Freedom of Information request by investigative journalists) has also helped filled the gaps.

[7] This measure excludes the self-employed and employees who would not describe themselves as temporary, but who work with a high degree of insecurity (job loss feared due to re-organization, contracting out etc.).

[8] Statistics Canada collects data on the numbers of self-employed with no employees, but does not ask if their employment status is by choice or because it was the only option available to them.

Topics: Economy, Employment & labour