Why we’re voting YES to new transit and transportation funding

By Seth Klein, Marc Lee and Iglika Ivanova

In the upcoming transit and transportation referendum, we think the benefits of a YES outcome outweigh the negatives for the following reasons:

- Referenda are a terrible way to make tax policy. But a referendum is nevertheless before Metro Vancouver residents, and we can’t afford to ignore it.

- We all have a legitimate list of grievances with Translink. But this referendum isn’t about Translink; it’s about new transit and transportation infrastructure and services. All the money raised from the proposed tax increase is earmarked for these new investments.

- Funding a third of Metro Vancouver’s transit and transportation plan via a 0.5 percentage point increase in the local sales tax isn’t perfect. But it is a reasonable approach.

- While sales tax increases can have a regressive impact (hitting lower-income households harder as a share of their income), in this case the new investments will go mainly to transit improvements, which benefit lower-income people in particular (since they rely more on public transit). As a result, the proposal is likely progressive overall.

- Given the political will (and enough pressure), the provincial government could off-set any negative impact by increasing the PST credit for lower-income people, boosting the low-income carbon tax credit, or extending the discount U-pass to lower-income people.

- These new investments are needed. A YES vote would significantly enhance transit services, boost local employment, and represent an important next step in local climate action.

In mid-March, residents of Metro Vancouver will receive mail ballots giving them a chance to vote in the region’s transit and transportation referendum. Ballots must be returned by mail by May 29.

Specifically, Metro Vancouver voters are being asked if they support a 0.5 percentage point increase to the provincial sales tax (officially known as the Congestion Improvement Tax), applied only in the Metro Vancouver region, in order to fund new public transit and transportation infrastructure.

The proposed tax increase would raise approximately $250 million per year,[1] and a cumulative total of over $2.5 billion over ten years. This would represent the region’s contribution towards an overall $7.5 billion capital plan for transit and transportation investments, with the balance of funding coming from the provincial and federal governments. New funding is not intended to go towards existing Translink operating costs, but rather, is entirely earmarked for new infrastructure and transit capacity.

The full $7.5 billion ten-year plan is a comprehensive approach to improve mobility for all residents in the region. It includes road improvements as well as transit infrastructure and expansion of services:[2]

- Basic investments just to keep up with population and employment growth ($449 million, of which $256 million is for keeping roads in good repair);

- A new Pattullo bridge ($978 million);

- Road upgrades and increased maintenance ($356 million);

- Upgrades and improvements to rail network ($853 million);

- Eleven new B-Line routes ($90 million) and additional service improvements and transit infrastructure, including a 25% increase in overall bus services, additional services for people with disabilities, and doubling of night bus services ($445 million);

- Three light rail lines in Surrey including one to Langley ($2 billion), and a new rapid transit line in Vancouver along Broadway ($2 billion); and,

- New bike routes and infrastructure ($131 million).

The overall goal is to ease congestion, and to provide more options and convenience to encourage people to switch from cars to public transit and other sustainable transportation modes like biking. As we saw so clearly during the 2010 Winter Olympics, a substantial increase in transit service can change how people choose to get around, with minimal disturbance or public outcry. The key ingredients are funding and political will.

While the issues behind the vote are complex, and there are reasonable concerns on both sides of the debate, on balance, we will be voting YES. The status quo of increasingly congested roads and over-crowded buses and trains is not an option –– our growing region desperately needs new transit capacity (for reasons related to both equity and climate), and we have to collectively pay for it one way or another.

This primer reviews some of the core issues arising from the transit referendum, and explains why we have decided that a YES vote is in the public interest.

Aren’t referenda a bad way to make tax policy?

Yes. Referenda are divisive, and a terrible way to make tax policy – just look at the havoc they create in California. We would not recommend future transportation plans or other public service improvements to be put to referenda. Instead, the CCPA has long called for a Fair Tax Commission for BC – a thoughtful process that would allow British Columbians to consider the entire tax system (not just one tax in isolation), and deliberate about how we want to raise the revenues we need in a way that ensures everyone pays their fair share.

Nevertheless, a referendum is before us. True, this referendum was forced by the provincial government – a misguided election promise in 2013, and against the wishes of the region’s municipal governments. But we don’t have the luxury of ignoring it. If the proposed sales tax increase is rejected, it will represent a major setback for vital public infrastructure, and for those of us who believe we need to pool more of our resources to invest in better and more accessible services.

What would this mean for lower-income people? Isn’t a sales tax increase regressive?

Sales taxes are rightly of concern to progressives due to their impact on low-income households. But the impact ultimately depends how it’s structured and what we use the money for.

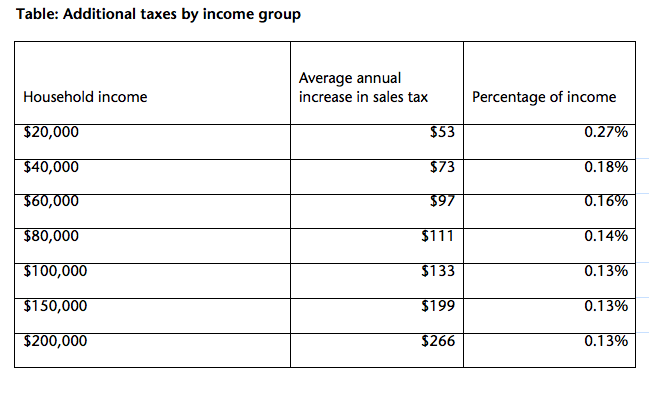

As the table shows, upper-income households would pay more in dollars because they consume more. However, sales taxes are regressive because lower-income households pay more as a share of their income because they spend all of their income (or more if they incur debt) on goods and services, whereas higher income households are able to save a portion of their income (and what they don’t spend in the local economy isn’t subject to the sales tax).

Importantly, the provincial sales tax (PST) does not apply to core necessities such as rent, groceries or child care, so much of what lower-income households spend their money on is exempt from the tax.

How we spend the additional tax revenue also matters. Because the new investments will go mainly to transit improvements, which particularly benefit lower-income people (since they rely more on public transit), the proposal is likely progressive overall. It’s not enough to look at the revenue side alone – we have to consider the full package. For example, Scandinavian countries tend to have much higher sales taxes than we do,[3] but their system of taxes and public expenditures greatly reduces inequality.

Importantly, any regressive impact of a sales tax increase could be easily fixed in one of three ways: by boosting the provincial sales tax credit lower income people can claim on their income tax returns; by increasing the low-income carbon tax credit for residents of Metro Vancouver, thereby giving lower-income households a larger quarterly payment; or the province could extend the discount U-pass to low-income people (it is currently only available to post-secondary students). This third option is particularly attractive, as it would not only reduce transportation costs for lower-income people who struggle with affordability, but also encourage transit use and enhance people’s mobility.

The BC government needs to offset the additional financial stress the proposed sales tax increase imposes on lower income families, and we should all advocate for this.

A modest sales tax increase may not be the perfect funding source for expanding transit infrastructure and services, but that’s not the option before us. Unlike the ill-fated HST and BC’s carbon tax, this proposed sales tax increase is not “revenue-neutral” – it will raise new revenues, and put that money to use in enhanced public services. This time, British Columbians are getting new valuable services in return for paying a slightly higher tax.

What does this mean for the local economy and jobs?

Every generation is tasked with making investments for the future. With a growing population, expanding transit infrastructure and improving service levels are essential to the region’s economy.

Because the proposed sales tax increase will raise new revenues and put that money to use investing in new infrastructure, it will be a net benefit to the local economy and local employment. That’s because part of the tax revenues raised will come out of reduced savings by high-income earners. The transportation investment plan will put that money to work, creating jobs in construction and in the operation of the new infrastructure.

Investments in high quality transit can save money for many households, and may even make car ownership unnecessary for some (households without a car save several thousand dollars per year). This means less money spent on vehicle purchases, insurance, maintenance and parking. [4] Our current auto-dominated transportation system also imposes costs in other ways: the negative health impacts of air pollution and from less active modes of transport; injury and death due to accidents; time wasted due to idling on congested roads and highways; and noise pollution.

The proposed new transit is particularly important to low-wage and immigrant workers, who often have to commute long distances for work, and who frequently work night shifts when transit options are limited (the proposal plan would see a doubling of night bus service hours). And it’s also of special importance to youth and seniors, who rely more heavily on transit.

What does this referendum mean for the climate?

The need for urgent action on climate change is one of the reasons we believe this referendum should pass. Transportation in Metro Vancouver accounted for 5.5 million tonnes of carbon emissions in 2010, more than half (53%) of the region’s total emissions.[5]

Skytrain and trolley buses, powered by clean BC Hydro electricity, are the lowest carbon forms of transportation in the province. Other Translink buses use fossil fuels, but these account for only a little more than 1% of transportation emissions in the region.[6]

High-quality – fast and convenient – transit capacity makes it easier for people to leave their cars at home. The share of trips by car in Metro Vancouver has been declining, although it still amounted to almost three-quarters of all trips in 2011 (higher in outer suburban areas).[7] That said, people are shifting onto public transit, with total passenger trips up 80% between 2000 and 2013.[8] As the region grows in population, more transit trips are inevitable, as there is only so much road space.

If Metro Vancouver residents vote NO, it likely means that investment in vital new public transit for our growing region will be further delayed by years.

Isn’t the governance of Translink problematic? Should we really be sending them more money?

We agree that Translink’s governance is badly in need of reform. People in Metro Vancouver need an accountable regional transportation authority that can deliver on the region’s needs. But that’s not a reason to vote against the proposed sales tax increase. All the new revenues will go into a separate fund earmarked for the new infrastructure and services proposed, and expenditures will be subject to independent audit and will be publicly reported.

The BC government must accept much of the blame for these governance problems. Translink’s unelected Board was imposed by the BC government on the region in 2008. The BC government has also imposed its own agenda for transportation in the region, including $3.7 billion spent on the new Port Mann bridge (this one bridge was equivalent in cost to 40% of the proposed new transportation package we will vote on in the referendum). A new Massey Bridge in the works to replace the tunnel will have a similar cost, and is oddly not subject to a referendum. The BC government also forced Translink to adopt the problem-plagued and expensive Compass faregate P3 system.

The No side is saying the sales tax increase is unnecessary, because municipal governments should be able to cover the $250 million a year by re-directing some of their future revenue increases.

This is a bogus argument. While revenues for Metro Vancouver municipal government will increase over the coming years, those revenues will be needed to cover inflation, population growth, and downloading of responsibilities from senior governments onto municipalities (for example, costs for wastewater treatment and policing which used to be covered by the federal government but now are paid for by municipalities).[9] And the existing backlog of infrastructure needs facing municipalities is massive. Local governments will be challenged enough to maintain existing services, let alone fund new infrastructure. The no side’s “alternative” funding plan would require budget cuts in other municipal services, like libraries and community centres.

So there’s our take. We shouldn’t be making tax policy by referendum, and the proposal before us is imperfect. If all this makes you very annoyed with the provincial government, we’re right there with you. But a choice is before us. And on balance, for all the reasons stated above, we think the benefits of a YES outcome outweigh the negatives.

If you feel aggrieved about the regressivity of a sales tax (and indeed of our whole tax system), then channel your energies into pushing for a fairer tax system (rather than voting NO on this proposal). We need new transit infrastructure, but we also need fair tax reform – and we will continue to argue for both. Join us in advocating for increases in lower-income tax credits, and for even bolder action on climate.

[1] Mayors’ Council on Regional Transportation, Regional Transportations Investments: A Vision for Metro Vancouver, December 2014.

[2] To see the detailed and costed plan, go to: http://mayorscouncil.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Mayors-Council_Appendices_June-12-2014.pdf

[3] For example, Sweden’s sales (or value-added) tax is 25%.

[4] Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Raise My Taxes, Please! Evaluating Household Savings From High Quality Public Transit Service, 26 February 2010, http://www.vtpi.org/raisetaxes.pdf

[5] Government of British Columbia, Community Energy & Emissions Inventory (CEEI), Metro Vancouver Regional District, 2010 year (updated Feb 20, 2014), http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/DownloadAsset?assetId=86FE4A1DD47A4B1A9AECA4ACCE74CE52&filename=ceei_2010_metro-vancouver_regional_district.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] Translink, How and Why People Travel, Regional Transportation Strategy Backgrounder #5, http://www.translink.ca/~/media/Documents/plans_and_projects/regional_transportation_strategy/Backgrounders/How_and_Why_People_Travel_Backgrounder.ashx

[8] Translink, Transit Ridership, 1989-2013, via Stephen Rees’ blog, https://stephenrees.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/transitridership.pdf

[9] Duffy, Robert, Gaetan Royer, and Charley Beresford, Who’s Picking Up the Tab: Federal and Provincial Downloading onto Local Governments, Columbia Institute/Centre for Civic Governance, September 2014.

Topics: Taxes