A carbon budget framework for BC: Achieving accountability and oversight

When it comes to climate change Canada’s leaders have been great at setting targets for far into the future and then failing to meet them.

Nationally, this pattern goes back to prime minister Brian Mulroney and has continued through prime ministers Jean Chrétien, Stephen Harper and now Prime Minister Trudeau. The Paris Agreement on climate change was signed in December 2015 yet two-and-a-half years later Canada does not have a plan to meet its 2030 pledge of a 30% reduction in carbon emissions (relative to 2005 levels).

In BC, former premier Gordon Campbell set a 2020 target of a 33% reduction relative to 2007 levels and a 2050 target of 80% below. As of 2015 (the last year for which we have data), BC emissions were a mere 2% lower.

BC experienced a recession-induced drop in emissions from 2008 to 2010, but since then emissions have increased every year. With 2020 almost in view, the new BC government has accepted that we will not meet the legislated 2020 target and has instead introduced new legislated targets of 40% below 2007 levels by 2030 and 60% below by 2040.

The problem with far-off targets is that it is easy for governments to forget about them as they will likely be out of office well before the day of reckoning.

Two-and-a-half years later Canada does not have a plan to meet its 2030 pledge.

In place of new climate actions, BC has been more interested in expanding natural gas production through liquid natural gas exports, which means a short-term fixation to take more carbon out of the ground and put it into the atmosphere.

That’s not to say we shouldn’t have targets and timelines. Of course we should. But setting them well beyond the lifespan of a typical government is clearly not working. What’s needed even more than long-term targets are short-term targets. That is, how much will we reduce emissions this year and next year and the year after that?

In short, we should establish carbon budgets. Planning for carbon reductions needs to be more like the conventional way we do fiscal planning: with an annual budget where a target is established at the start of the year along with actions on how it will be achieved (including credible investments that create jobs in green infrastructure), and routine monitoring and reporting. That is, it should be more like the annual BC fiscal budget process that sets out rolling three-year plans with an independent auditor-general to confirm if fiscal reporting is legit.

Carbon budgets in the UK

A precedent for this type of carbon budgeting approach can be found in the United Kingdom.

The UK passed a Climate Change Act in 2008, which set a 2050 emissions target of 80% below 1990 levels along with a carbon budget system based on three five-year budget periods going forward at any time. For example, the first carbon budget was for 2008 to 2012 (and was achieved), and the country is on track to meet its second (2013 to 2017) and third (2018 to 2022) carbon budgets. The UK also implemented a carbon accounting system, including international transfers and rules for moving available budget from one year or period to the next.

To provide independent oversight, the UK created a publicly funded Committee on Climate Change (CCC), which makes recommendations on mitigation measures, monitors outcomes and engages in research. The CCC’s June 2017 report to Parliament, for example, runs 200 pages, provides a detailed analysis of progress to date, projects the gap between current policies and future targets, and outlines sector-by-sector recommendations to achieve the targets. The UK government is required to consult the CCC and there are substantial reporting obligations on the part of government. Overall, it’s a level of accountability unseen in Canada.

More recently, in October 2017 the UK government released a new Clean Growth Strategy, which, at 167 pages, is far more detailed than its Canadian equivalent, the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. (Both governments have rhetorically wrapped themselves in the vague language of “clean growth” but that’s a topic for another post.) The CCC’s assessment of the strategy is anchored in the context of the UK’s carbon budgets and concludes in a summary:

Gaps to meeting the fourth [2023 to 2027] and fifth [2028 to 2032] carbon budgets remain. These must be closed. Whilst the Strategy sets out a ‘2032 Pathway’ for sectoral emissions that would just meet the fifth carbon budget, there is no clear link to the policies, proposals and intentions that the Strategy presents. Our assessment of the policies and proposals set out in the Strategy indicates that, even if these deliver in full, there remain gaps of around 10-65 Mt CO2e to meeting both the fourth and fifth carbon budgets on the basis of central projections.

Remarkably the UK has been the most successful country in the world at reducing its emissions, which have dropped to 42% below 1990 levels and are now at 1890 levels (yes, 1890, that is not a typo). This is largely due to the low-hanging fruit of phasing out coal-fired electricity. Challenges remain in reducing emissions from industry, buildings and transportation.

While climate action is not perfect in the UK, this type of forward thinking and accountability would be most welcome in BC and Canada as a whole. Carbon budgets clearly have promise in providing clarity and discipline, especially when accompanied by rigorous independent oversight.

What would this look like in BC?

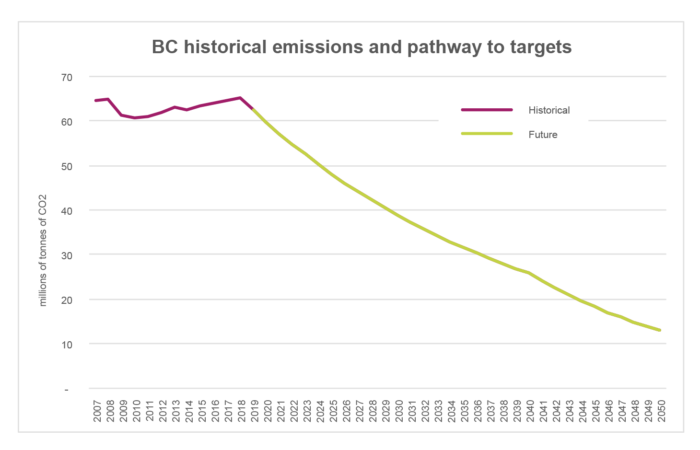

To illustrate such a framework for BC, let’s start with historical emissions, then the BC government’s new legislated targets of a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030, a 60% reduction by 2040 and an 80% reduction by 2050 (all relative to 2007). The first question is how much do emissions have to decrease each year in order to meet the target with steady and consistent reductions? There’s a lag between when data are available with the most recent data being from 2015. This lag should be addressed in concert with the new carbon budget planning framework. I estimate modest increases in emissions in 2016, 2017 and 2018 consistent with emissions growth in recent years (just under 1% per year).

For a smooth pathway to meet the 2030 target, emissions need to drop 4.22% per year starting in 2019. That is, we need to plan for emissions next year (2019) to be 4.22% lower than this year; then for 2020 emissions to be 4.22% below 2019 and so on to 2030. After 2030 the rate of change slows a bit to 4.0% to meet the 2040 target, then for 2041 to 2050 larger annual percentage drops of 6.7% per year are needed. BC’s 2050 legislated target requires us to limit BC emissions to just under 13 million tonnes of CO2.

Because we are reducing emissions each year the actual annual reduction (in tonnes of CO2) falls over time. In 2019 emissions need to fall by 2.75 Mt below 2018 emissions; in 2030 they need to drop by 1.7 Mt below 2029 emissions; and by the time we reach 2050, the annual drop is 0.9 Mt below 2049. This approach allows BC to harvest the low-hanging fruit early on and get to the most challenging emission reductions in later years.

Sources: BC Greenhouse Gas Inventory for historical emissions to 2015; author’s calculations for emissions 2016-2015.

This is a helpful approach because it breaks down the future big drop in emissions into manageable chunks. A 4.22% annual drop is not necessarily easy but people can wrap their minds around it.

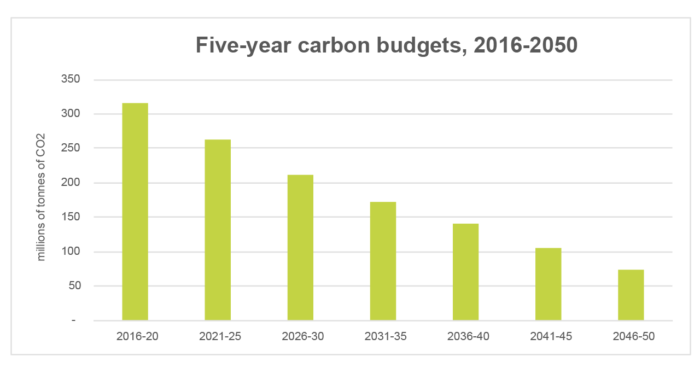

The next innovation is to bring in five-year budgets like in the UK. This structure allows some flexibility in emission reductions due to changes in the business cycle or recognizing that some major investment decisions are “lumpy” (that is, large reductions achieved once implemented). To keep things simple I have grouped five-year carbon budgets to line up neatly with the 2050 target, but many alternative variations are possible. My first carbon budget period is 2016 to 2020 and allows a five-year total of 314 million tonnes (Mt) of emissions. In the next five-year period, 2021 to 2025, the total permissible emissions fall to 252 Mt. And so forth.

The nice thing about this framework is that it more closely aligns with the political cycle. Politicians can’t pat themselves on the back so easily for making grand statements; they would actually need to deliver. This framework would make it easy to tie a salary bonus for a minister and/or premier for meeting a target.

I should note that by even doing this exercise, BC is laying claim to 1.2 billion tonnes (gigatonnes or Gt) of emissions between now and 2050—if we meet our GHG targets. At a “social cost of carbon” of $50–200 per tonne of damages, that’s $60–240 billion in climate damages!

The world actually needs much more ambition in terms of emission reductions from rich places like BC. This year, as part of the Paris Agreement, countries are to do a “global stock-take” of commitments with an aim of putting more aggressive pledges on the table. For BC to meet the 2030 target will be hard enough, but full decarbonization by 2050 is better aligned with where climate science tells us we need to be. With the framework above in place, it would be relatively straightforward to put the 2030 to 2050 trajectory on the more aggressive path to full decarbonization.

We also need to start accounting for the emissions from carbon we extract and export for burning in the US or Asia or wherever else and not counted in BC’s greenhouse gas inventory. A supply-side version of carbon budgets would look at fossil fuel extraction and exports with a view towards putting those amounts on a downward trajectory as well.

The key is to actually commit to reducing emissions. Every year.

As we progress we may need to tighten up the carbon budget to be more aligned with climate science, but at least we would be moving in the right direction. A new framework of carbon budgets, along with independent auditing and oversight, would make our boasts of “climate leadership” much more credible.

Topics: Climate change & energy policy, Features