Basic income panel calls for major reforms to income security in BC

When the final report of BC’s Basic Income Panel came out in January, the media coverage was largely reduced to a few dismissive headlines that the panel had rejected basic income.

Behind the headlines, however, is a comprehensive and thoughtful analysis of the state of poverty in BC and the large number of existing programs, all anchored in 40 background research papers commissioned by the panel and laid out in a 500-page report.

In its deliberations, the panel starts by articulating a justice framework for income security and poverty. On justice, the panel of three academic economists1 makes a welcome call for a “just society” in BC. Philosophically, this means “providing the means of self-respect and social respect” and the ability for people to “feel like they have autonomy, control and social connection.”

The panel makes 65 recommendations to fight poverty—covering income security, public services and the labour market—that the BC government should implement, starting in the 2021 budget. The panel does support a basic income for people with disabilities and makes many suggestions to transform the Disability Assistance program in that direction. The panel also calls for a targeted and transitional basic income for youth formerly in foster care, along with other institutional changes aimed at achieving much better outcomes for the approximately 1000 youth aging out of care each year.

What did the panel reject and why?

Part of the challenge is that there are many flavours of basic income. Each of these variants has a different cost and the panel ran many simulations to evaluate the fiscal implications, which can balloon substantially. For example, a universal basic income (that is, paid to each working age British Columbian) of $20,000 per year would cost $51 billion, essentially doubling the BC budget. A refundable tax credit model—which provides the same maximum amount but is reduced as income rises—would cost $8 to $17 billion (depending on how quickly the benefit is phased out for people with higher incomes).

Ultimately, the panel argues for more targeted measures building on existing programs and systems, which would fundamentally achieve the same objectives at a much lower cost. Basic income is not just money, however. In the panel’s view, basic income supports individual autonomy but de-emphasizes other characteristics of justice: community, social interactions, reciprocity and dignity.

Reduce bureaucratic hurdles

BC’s income assistance program for working age adults is dealt some particularly harsh criticism. The panel calls for higher welfare rates, including making permanent the bonus $300 COVID supplement. This was reduced to only $150 in January and led to a backlash. More recently, both Temporary and Disability Assistance have been permanently increased by $175 above pre-COVID levels. At a minimum the full $300 should be made permanent, and benefits should be indexed to inflation so as not to erode over time, according to the panel.

The panel also calls for fewer bureaucratic hurdles for people in need to improve their access to support. This includes measures to smooth the transition from income support to work by lowering the “welfare wall”—the reductions in support and services as one takes on paid work. For example, a dollar lost in welfare income for each dollar earned in the labour market, and there are losses of non-cash health care benefits as one transitions to work.

The panel recommends an enhanced earnings supplement (or wage subsidy) for working poor households. This would include a provincial reconfiguration of the federally delivered Canada Workers Benefit along with a provincial top-up for low-income adults without children.

The panel calls for higher welfare rates, including making permanent the bonus $300 COVID supplement.

Expanding the suite of extended health care services available to all low-income households (not just those on welfare) is both practical and fair. In these areas there is a gap for working poor households, as a large share of the population is covered through private, workplace-based plans, while there is public coverage for people on welfare. Publicly insured dental services are singled out as a particularly valuable benefit to extend to the working poor.

Housing affordability is a top priority. The panel calls for a more coherent support system for low-income renters. Manitoba’s innovative Rent Assist program is flagged as one BC should emulate. This program pays the difference between 30% of one’s income and 75% of the median rent in the city (as opposed to one’s actual rent), which means landlords cannot pocket the benefit as higher rent.

Interestingly, the panel strays from income support towards labour market reforms, noting a policy gap in the “dignity and accessibility of work” in BC, which includes wages and working conditions for people in low-wage or low-skill jobs. The panel calls for better “predistribution”: higher incomes through the labour market for households earning a low income. These can be the result of policies like better regulation of employment standards for gig workers and achieving higher unionization rates in the low-wage service sector.

What’s the bottom line?

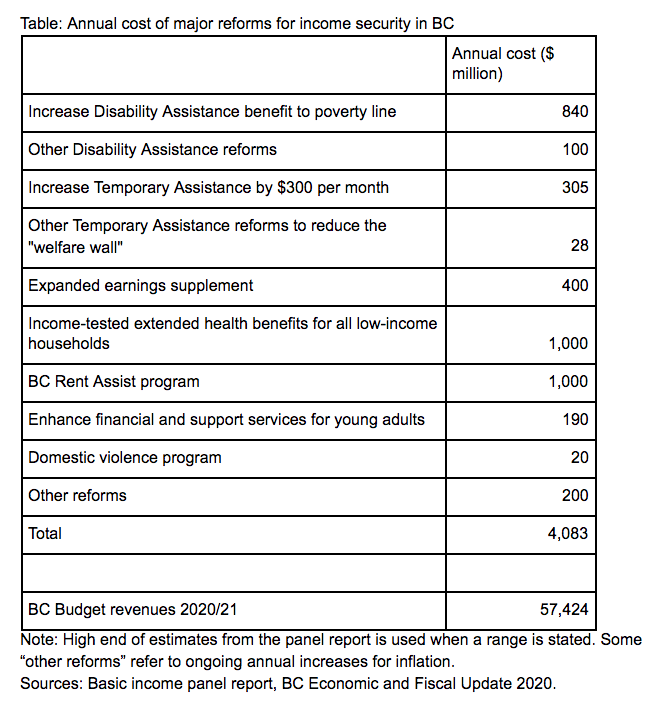

The estimated total cost of various anti-poverty measures would be in the $3.3 to $5 billion per year range, representing a 5% to 8% increase in the BC budget (see table). Some of this could be recouped from existing expenditures, such as the Home Owner Grant ($830M/yr), which goes to many affluent homeowners. The panel also recommends combining the various existing BC tax credits (such as the PST credit and climate action credit) into a single “Dogwood benefit.”

At the end of the day, the panel finds that basic income is not a panacea. More cash alone is not sufficient to ensure the essential foundations for individual autonomy, self-respect and dignity. Supportive and wrap-around public services, supports to work and earnings, and a more conducive labour market are also essential so that no one is left behind.

And as budgets are about the choices we make, the panel is concerned that a costly basic income would compromise spending on essential public services needed for a just society, or that such a basic income would not be resilient to the next right-wing government that would simply take it away.

While this report is not likely to end the debate about basic income, it provides a solid research base for future discussions and a framework for thinking about poverty reduction policy. Some basic income advocates have been critical of the report’s findings, but it is notable that, in spirit, the panel supports the same key concerns as advocates. If implemented, the panel’s report recommendations would drive a major reduction in poverty in BC.

Note

1. Disclosure: Panel chair David Green is a long-time Research Associate of the CCPA’s BC office.

Topics: Economy, Employment & labour, Poverty, inequality & welfare