A Big Fracking Mess: As Site C dam construction bogs down in geotechnical problems, thousands of earthquakes triggered by fracking operations occur nearby

Earthquakes triggered by natural gas industry fracking operations near BC Hydro’s troubled Site C dam construction project are far greater in number than previously thought, raising troubling questions about whether they are adding to the already formidable geotechnical challenges at the site.

Not only are more earthquakes occurring in proximity to the costliest public infrastructure project in British Columbia’s history, but many of the fracking-induced tremors—including one that shook the ground so hard two years ago at Site C that workers were ordered to evacuate—are occurring in a fault-riddled zone to the south of the dam that geoscientists have warned can become quickly unstable during fracking operations.

Now, thanks to the work of David Leversee, an experienced mapper, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives is able to show for the first time just how many earthquakes are occurring in proximity to the troubled dam project, which is mired in controversy due to recent revelations about a host of new “geotechnical problems” at the site—problems that could yet prove the project’s undoing.

In 2017 and 2018 alone, there were 6,551 earthquakes in the region equal to or greater in magnitude than 0.8. That number vastly surpasses the 71 earthquakes identified in the same region in Canada’s national earthquake database, which is maintained by Natural Resources Canada (NRCAN) and is typically considered the go-to voice on earthquakes in the country. In addition to those thousands of earthquakes, there were more than 4,100 other very small magnitude seismic events in the same area that registered under 0.8 magnitude. Almost all of the earthquakes occurred in the geologically sensitive zone where Site C is located and where fracking companies have been extremely active.

Not only are more earthquakes occurring in proximity to the costliest public infrastructure project in British Columbia’s history, but many of the fracking-induced tremors… are occurring in a fault-riddled zone to the south of the dam that geoscientists have warned can become quickly unstable during fracking operations.

The much higher figures are derived from the recent work of a team of scientists, led by Ryan Visser a physical scientist and seismic analyst with Natural Resources Canada, who analyzed data from a greater number of seismographs (earthquake monitors) than are in the NRCAN network. The expanded network included seismographs owned by some of the very companies that did the fracking jobs that are triggering the earthquakes, as well as monitors installed by universities and regulatory agencies. The scientists used the expanded network to also identify earthquakes at much smaller magnitudes than previously reported.

Pump it Up: Welcome to Canada’s fracking earthquake capital

Leversee used the same data to plot the earthquakes onto a map. The map shows that much of the area to the south of the Site C dam is riddled with faults in the shale rock where fossil fuel companies have pressure-pumped hundreds of millions of litres of water into the earth. That pumping has touched off thousands of earthquakes over a very short time period, including a 4.5 magnitude earthquake in November 2018 that led to the evacuation of workers at the Site C project.

Map 1. Credit: David Leversee.

The zone is part of the natural gas-rich Montney Formation, which has the dubious distinction of having “hosted” more earthquakes triggered by fracking operations than any other region in Canada, according to a recent study led by geophysicist Marcos Roth.

Almost all of the earthquakes occurred in the geologically sensitive zone where Site C is located and where fracking companies have been extremely active.

The earthquakes blanket much of the Kiskatinaw Seismic Monitoring and Mitigation Area or KSMMA. The area is named after the Kiskatinaw River, a tributary of the nearby Peace River where the Site C dam project is located. The KSMMA is riddled with underlying faults. Those faults, according to two independent geoscientists who reported in 2019 to British Columbia’s Oil and Gas Commission, can easily become “critically stressed” with just small increases in the pressure at which oil and gas companies pump massive amounts of water, sand and chemicals underground during fracking operations to “liberate” trapped natural gas and valuable liquids including light oil and condensate.

It was one of those pumping operations at a natural gas well site 20 kilometres south of the Site C project that touched off the November 2018 earthquake.

FOIs reveal seismic risks to BC Hydro’s Peace River dams

In early 2020, the CCPA published two lengthy investigations based on documents obtained through a Freedom of Information request filed with BC Hydro. The documents showed that dam safety officials and engineers at the Crown power utility had serious concerns about the damage that could be caused to its two existing dams on the Peace River.

The first of the two pieces flagged concerns within BC Hydro about the Peace Canyon dam, which is about 80 kilometres upstream of the Site C project. FOI documents revealed that should a strong enough earthquake be triggered near the Peace Canyon dam it could set in motion events that brought the concrete and steel structure down. The same piece also noted concerns within BC Hydro about the potential vulnerability of the WAC Bennett dam. The massive earth-fill dam, which is the height of a 60-storey building and impounds the world’s seventh-largest reservoir by water volume, lies upstream of Peace Canyon.

FOI documents revealed that should a strong enough earthquake be triggered near the Peace Canyon dam it could set in motion events that brought the concrete and steel structure down.

The second of the two reports, focused on a disposal well operation near the Peace Canyon dam. Disposal wells are where waste liquids generated during the fracking process are pumped deep into the earth for disposal. The disposal well was only a short distance from the dam. FOI documents obtained from BC Hydro showed that a 5.5 magnitude earthquake near enough to the Peace Canyon dam could have “significant” consequences for the concrete and steel structure. The same piece also detailed events at the natural gas fracking operation that triggered the November 2018 earthquake and concerns at Site C.

A costly dam and mounting “geotechnical problems”

The latest revelations about huge numbers of earthquakes near Site C come as details emerge about a disturbing number of allegedly new “geotechnical problems” at the troubled megaproject.

Almost from the start, Site C has faced setbacks, virtually all of which involved the notoriously unstable terrain in which the third dam on the Peace River is being constructed.

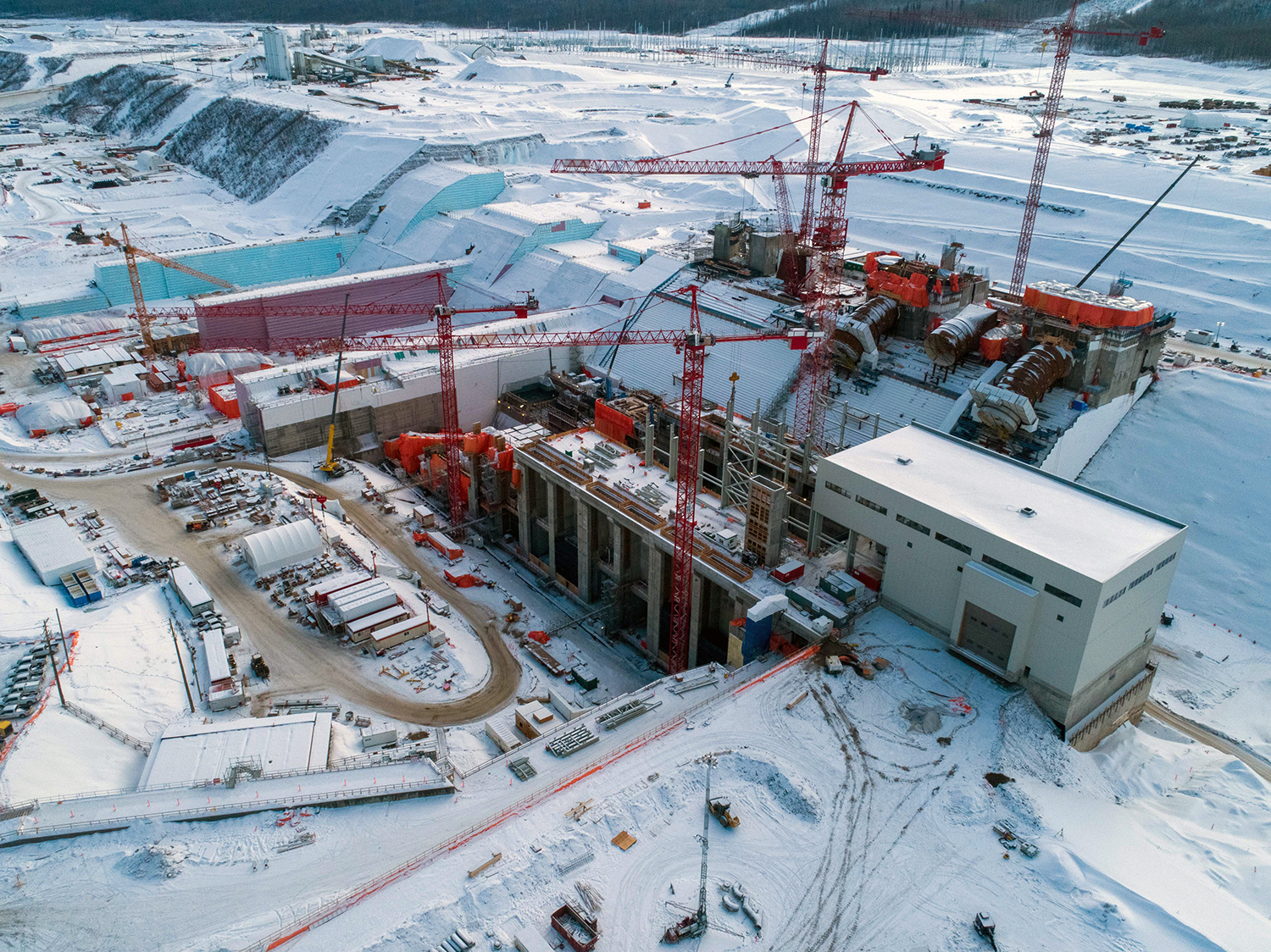

In early August, the provincial government announced that BC Hydro had discovered a host of “geotechnical problems” at the Site C project. Projected costs for the project had already risen from $6.6 billion to $12 billion, before the problems were identified. Credit: BC Hydro Dam site gallery (2020) slide 6/64.

In the winter of 2017, a 400-metre-long “tension crack” opened on the steep northern bank of the river, leading to a lengthy and costly delay as engineers scrambled to come up with plans to stabilize the bank, then re-excavate it and truck away thousands of tons of additional earth.

A major landslide occurred just downriver from the dam site a year later, tearing up the road to Old Fort and forcing the evacuation of nearly 200 residents—a landslide still being investigated with no end in sight by BC’s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources.

The latest revelations about huge numbers of earthquakes near Site C come as details emerge about a disturbing number of allegedly new “geotechnical problems” at the troubled megaproject.

Frequent problems occurred drilling and cementing the two lengthy diversion tunnels that are required to divert the river so that the dam itself can be built, problems that also plagued the drilling of a kilometre-long drainage tunnel needed to divert water around dam infrastructure. Making matters worse, the drilling and cementing of a second drainage tunnel has barely started, even though work was to commence in August 2017 and end in November 2018.

As the problems pile up, so do the financial challenges for BC Hydro, which must eventually be passed along to taxpayers. Site C’s original estimated cost was $6.6 billion. But many experts now believe the final bill for Site C will be $12 billion or more—a projection that aligns with what the independent BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) said three years ago.

Site C problems: BC Hydro won’t even hazard guess at costs

According to recent reports that BC Hydro filed after months of delay with the BC Utilities Commission—the first covering the last three months of 2019, the second covering the first three months of 2020—the new geotechnical problems are legion and involve making changes or improvements to key components of the dam including the massive, roller-compacted concrete buttress behind the dam’s powerhouse, the powerhouse itself, spillways, drainage infrastructure, and much more.

Major components of the Site C dam including the powerhouse, sloping roller-compacted buttress, and drainage infrastructure now face new geotechnical challenges, according to BC Hydro’s recent filings with the BC Utilities Commission. Credit: BC Hydro Dam site gallery (2020) slide 57/64.

“Hydro doesn’t even try to guess at a cost, except to predict it will be ‘much higher than initially expected,’” veteran Vancouver Sun political affairs columnist, Vaughn Palmer, wrote of the most recent revelations.

All of which makes the troubling number of earthquakes induced by fracking operations not far from Site C of such concern. Scientific study after scientific study has shown that the oil and gas industry industry fracking and disposal well operations trigger earthquakes.

As the problems pile up, so do the financial challenges for BC Hydro, which must eventually be passed along to taxpayers.

Like northeast British Columbia, the State of Oklahoma was not known for having many earthquakes until the fracking industry arrived. But in 2011, one of the largest earthquakes to be associated with fossil fuel industry activities anywhere was triggered at a disposal well site in the state. The quake shook the ground in 17 US states, buckled a highway in three places, damaged homes and injured two people. Scientists who studied the event later concluded that the cumulative effect of 18 years of continuous pumping deep into the earth at the well site had set the stage for the strong quake.

To date, the earthquakes in BC triggered by fracking operations have yet to reach that magnitude. But there is nothing to prevent such an event from happening. And the big question is what that might mean for geotechnically problematic projects such as Site C.

The information on earthquakes in proximity to the dam is derived from data in two recent scientific studies.

Adding it up: Just how many earthquakes may fracking be triggering?

The two studies were both prompted by concerns that fracking is playing an increasingly important role in triggering earthquakes; that such induced earthquakes are on the rise, and that information from many seismographs is not being collected in one place to provide a more comprehensive picture of what, exactly, is going on.

What both studies do is combine information from the national earthquake database maintained by NRCAN and other seismographic networks.

Scientific study after scientific study has shown that the oil and gas industry industry fracking and disposal well operations trigger earthquakes.

The first of the two studies to draw on information from a vastly expanded seismographic network looked at earthquakes in northeast BC and western Alberta between 2014 and 2016.

The study, published by the Geological Survey of Canada in 2017, concluded that in those three years, the NRCAN database reported a total of 1,513 seismic events, while the actual number was three times higher at 4,916.

During that time frame, there were five notably strong earthquakes in the study area: a magnitude 4.52 event on August 4, 2014 west of Fort St. John; a 4.36 magnitude event on January 23, 2015 near Fox Creek; a 4.59 event also near Fox Creek on June 13, 2015; a 4.55 magnitude event west of Fort St. John on August, 17, 2015; and finally a 4.39 magnitude event located near Fox Creek on January 12, 2016.

Using the same data gathered in that report, Leversee narrowed the study area down to a smaller area of land that included the Peace River region and the WAC Bennett, Peace Canyon and Site C dams and then pinpointed all of the earthquake epicenters.

Map 2. Credit: David Leversee.

Leversee’s analysis showed that in the smaller area there were 2,983 earthquakes—a much larger number than the 347 seismic events recorded in the NRCAN database. In other words, nearly nine times more earthquakes—including earthquakes nearby Site C—occurred than were captured in the NRCAN record.

In addition to seismic events near Site C, there were also earthquakes under or beside the massive Williston Reservoir, which is impounded by the WAC Bennett dam. FOI documents obtained by the CCPA, show that BC Hydro officials believe an unusual and unexplained water movement at the reservoir in 2012 may have been attributed to fracking operations.

In other words, nearly nine times more earthquakes—including earthquakes nearby Site C—occurred than were captured in the NRCAN record.

The second and more recent of the two scientific studies that Leversee drew on to generate his maps looked at a much smaller area of land than the first. That report, as noted earlier, looked at earthquakes in the years 2017 and 2018. In total, that report detected 10,692 earthquakes in the study area, a dramatically higher number than those identified in the first report even though the study area was smaller.

The authors of the more recent study noted that while there had been an overall decline in drilling and fracking operations in Western Canada during that time, drilling and fracking remained intense in the Dawson Creek and Fort St. John areas because of the high percentage of valuable gas liquids, including condensate, found in the region’s underlying shale rock. (Condensate from northeast BC is highly sought after by Alberta’s tar sands industry.)

As a result of that ongoing drilling and fracking, many earthquakes occurred in the highly sensitive and geologically unstable Kiskatinaw zone near the Site C dam.

A fracking carpet bombing campaign

A significant question, for which there may be no readily available answer, is just what the longer term implications of those thousands of small earthquakes occurring over relatively short periods of time in a confined, highly sensitive area may mean. Could increasing numbers of smaller earthquakes be setting the stage for bigger earthquakes later on? And how big could those earthquakes one day be?

In February 2019, an independent panel of three scientists issued a report on fracking to the BC government. The report noted several troubling unknowns, including just how strong an earthquake could one day be triggered by fracking.

That is a disturbing finding, considering that the same report noted that there is scientific evidence that the cumulative impact of multiple fracking jobs is an increased likelihood of bigger earthquakes later on—a finding of particular relevance to Site C, where geotechnical troubles abound already and could be made much worse should a significantly strong earthquake occur nearby.

A significant question, for which there may be no readily available answer, is just what the longer term implications of those thousands of small earthquakes occurring over relatively short periods of time in a confined, highly sensitive area may mean.

While market downturns and the global COVID-19 pandemic have wreaked havoc upon many sectors of the economy, including the fossil fuel sector, the other troubling news for BC Hydro at all three of its Peace River dams is that if and when the LNG Canada liquefied natural gas plant and connecting Coastal Gas Link pipeline are completed, much of the gas entering that pipeline will originate in the very region where large numbers of induced earthquakes are already occurring.

Stephen Rigbey, the former head of dam safety for BC Hydro, likened what lies ahead for the Peace River region to a “carpet bombing” campaign. It was not hyperbole. According to a recent report published by the CCPA and written by earth scientist, David Hughes, who worked for 32 years at the Geological Survey of Canada, natural gas production in BC “is projected to grow by 87 per cent over the 2019-2040 period.”

That translates to huge increases in fracking in a seismically fragile region where BC’s biggest publicly funded infrastructure project is now mired in geotechnical problems that at the very least could prove prohibitively expensive to fix. If they can be fixed at all.

Call it one big fracking mess.

This post is part of the Corporate Mapping Project, a research and public engagement project investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry in Western Canada, led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (BC and Saskatchewan Offices) and Parkland Institute. This research is supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the Minor Foundation for Major Challenges.

Topics: Environment, resources & sustainability, Fracking & LNG, Transparency & accountability