Can Metro Vancouver afford more equitable access to transit for youth and low-income households?

In Metro Vancouver the #AllOnBoard campaign is making the case for equitable access to transit for youth and low-income households. The campaign is calling for: (1) free transit for those under age 18; and, (2) a sliding-scale pass for adults based on income. Discounting transit fares deserves to be part of a poverty reduction plan, and it would also reduce the harms associated with ticketing for fare evasion by ensuring low-income and at-risk individuals do not develop the life-long harm of bad credit due to inability to pay fines.

If the #AllOnBoard campaign is successful, Metro Vancouver would follow other jurisdictions that have made transportation equity a priority by restructuring their fares. For Calgary’s sliding scale transit pass, the lowest-income residents now pay just $5.30 per month. In Halifax, low-income monthly passes are available for half the cost of the regular adult rate. Across the border, Seattle has both a discounted low-income pass and also voted in 2018 to give high school students free bus passes.

There is a strong case to be made for changing the fare structure as a transportation equity and poverty reduction measure, and there are very achievable options for funding such a plan. Mobility at a reasonable cost is central to social and economic well-being. We know that not everyone can drive due to age, disability or low income. Transit is an essential public service that provides mobility for residents and access to employment, shops, public and private services, amenities and entertainment. As the CCPA’s Manitoba Office has eloquently stated, transportation equity is “the idea that everyone, regardless of physical ability, economic class, race, sex, gender identity, age or ability to pay should have access to public transit and active transportation options.”

The current model of transit funding

Fare revenue for TransLink covers just over half of the cost of operating transit, with the remainder coming from regional taxes (more on these below). This does not mean drivers subsidize transit users: drivers are also subsidized through public expenditures on roads and other infrastructure, and they impose additional costs on society through noise, pollution and accidents. In addition to greater mobility, by subsidizing public transit we reduce congestion on roads along with air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

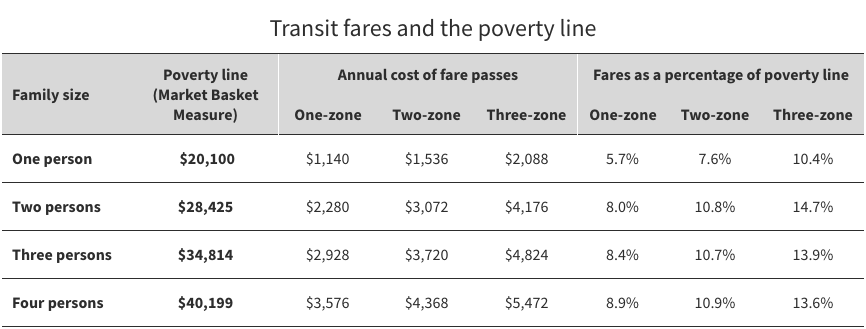

Access to transit remains a challenge for people with low incomes. A monthly fare pass can represent a sizeable share of a household’s income, depending on family size and number of zones travelled. The table below illustrates the cost of transit passes for those with an income at the poverty line (as defined by the Market Basket Measure). The cost of a transit pass ranges from between 5.7% of household income for one person going one zone, up to 13.6% of income for a family of four (two adults, two kids) going three zones.

Notes: The annual cost of fare passes is based on the cost of a one-zone fare pass at $95 per month, a two-zone fare pass at $128 per month, a three-zone fare pass at $174 per month, and a concession fare of $54 per month. For a one- and two-person household we assume both residents are working adults, and for three- and four-person families we assume the remaining household members are school-aged children eligible for a concession fare. Sources: Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0066-01 Market Basket Measure (MBM) thresholds for the reference family by Market Basket Measure region, component and base year. TransLink. This table updates 2007 CCPA research by Stuart Murray.

The high cost of housing in the region also adds to household transportation costs when people need to move farther away from work in order to find affordable housing, in turn having to pay multiple-zone fares. Already, a large share of households near SkyTrain stations are low income, although residents in such housing are increasingly threatened with displacement due to redevelopment.

A 2015 CCPA study, Moving Beyond the Car, by Arlene McLaren found that many families were multimodal (they used a variety of transportation options depending on the situation). They wanted better transit options in order to drive less, but found that “service was often not adequate, child-friendly or affordable.” With current fares, a parent travelling with two children might pay more for a return trip downtown by transit than they would if they drove. Free transit for riders under 18, as the #AllOnBoard campaign is calling for, would make getting around more affordable for both youth and their families.

While TransLink states that poverty reduction is not part of its mandate, ensuring equitable access to transit is, in practice, already baked into TransLink’s fare structure. Very young children (four and under) travel for free, and discounted “concession” fares are available for ages five to 18, and for seniors (over 65). In addition, the provincial government funds a BC Bus Pass program, a discounted pass for about 100,000 people with disabilities, at a cost of approximately $80 million per year province-wide (note: the BC Bus Pass does not cover other people on social assistance).

What would it cost?

TransLink estimates that free transit for all riders under 18 would cost about $35 million per year (in lost fare revenue), and a sliding scale for low-income adults would cost a further $25–40 million per year. For the sliding scale, the precise cost will depend on how much a subsidy is provided at different income levels, and how higher fares for multiple zones are treated.

Eliminating or reducing fares will also lead to increased ridership, and therefore higher costs for TransLink to provide additional service. Because youth and people with low incomes are already highly transit-dependent, the effect is likely to be small during peak hours of operation. There may be a greater impact during off-peak hours as people take more discretionary trips, although this can more easily be accommodated within existing system capacity.

Pinning down the exact amount of increased expenditures is difficult (see this review of the various factors at play). We can estimate $75 million in forgone fare revenues (using the high end of TransLink’s estimates) and $25 million in increased services (a 2.4% increase in transit expenditures of just over $1 billion in 2017) for a total of $100 million to finance implementation of the campaign.

BC government funding

There is a compelling case for the BC government to fund the #AllOnBoard campaign ask as part of their poverty reduction strategy, TogetherBC. The cost of providing free transit for youth under 18 and a sliding scale pass for lower-income adults is both good social policy and fiscally very achievable: the 2019 BC Budget includes an underlying budget surplus of $1.5 billion for the 2019/20 fiscal year, while transportation expenditures in the Budget are estimated to be $2.3 billion in 2019/20.

Similar amounts of money have recently been allocated for the benefit of drivers (who notably do not have to pay any fare for accessing the region’s road network). BC Budget 2019 added $42 million (over three years) to subsidize the adoption of low- and zero-emission vehicles through rebates. This is on top on tens of millions going back to 2011 when the program was first introduced. Such subsidies go to already affluent households in the position to buy a new car, and much of these public funds end up going to people who would have bought them anyway.

The cost of providing free transit for youth under 18 and a sliding scale pass for lower-income adults is both good social policy and fiscally very achievable.

Many drivers also benefitted from the 2017 elimination of tolls on the Golden Ears and Port Mann bridges. This move cost TransLink more than $50 million per year in lost toll revenue from the Golden Ears Bridge (replaced by the provincial government through a revenue transfer to TransLink) and cost the BC government $135 million per year in lost revenue from the Port Mann bridge.

A BC government commitment, as part a provincial poverty reduction strategy, could thus compensate TransLink directly with a transfer of approximately $100 million to replace lost fare revenues. Parallel programs should be developed for transit in other parts of BC.

TransLink financing options

If the BC government is unwilling to support fare reductions, TransLink has many options to self-finance the #AllOnBoard campaign ask.

TransLink could reduce the budget for TransLink police, which cost $37 million in 2017, with savings used to fund the #AllOnBoard campaign ask. Much of the work of the TransLink police for fare evasion would no longer be necessary, as it is likely youth and low-income individuals who primarily evade fares due to poverty. An independent audit of fare evasion activity should be developed to inform public policy, but given the available numbers such an audit would likely show that fare evasion activities fail a cost-benefit test.

While TransLink claims it is losing millions in fare revenue due to evasion, the transit authority issued only 14,500 fare evasion tickets in 2018, or $36,250 in lost revenue (assuming $2.50 per fare). Total infractions would need be 27 times higher to yield $1 million in lost revenue. Only when translated to fines at $173 per offence does 14,500 tickets yield $2.5 million in potential fine revenue, but this is a gross amount. Actual (net) revenue will be less that this because of the costs of collection, the share of people who cannot afford to pay (including many repeat offenders), and the substantial costs of policing fare evasion.

Moreover, ticketing is excessively punitive, with additional personal costs for those ticketed, in the form of bad credit and inability to get a driver’s license, which further entrench poverty (note that a fare evasion fine is much more costly than a parking ticket). Seattle and Portland have shifted to allowing community service in lieu of paying a fine.

In addition to reconsidering fare evasion expenditures, TransLink also has its own revenue options that could support the #AllOnBoard campaign ask. Established in 2000 as a regional body with its own revenue sources to fund operations, TransLink has its own regional tax base, including: property tax, fuel taxes, parking sales tax, a vehicle levy, and benefiting area charges (an additional property tax in the immediate vicinity of transit stations).

TransLink’s ability to tap certain revenue sources is limited by legislation, with further increases requiring approval by the BC government. Fuel taxes are in this category, with TransLink currently receiving 18.5 cents per litre of fuel tax within Metro Vancouver region (as of April 2019). The regional parking sales tax was increased in 2018 from 21% to 24%. Benefitting area charges have never been implemented, but are increasingly being looked at as a mechanism to support expansion of the transit system. A vehicle levy (annual charge per car) was proposed in 2000 then killed by the BC government.

TransLink also has its own revenue options that could support the #AllOnBoard campaign ask.

A good candidate for revenue generation is the regional property tax collected by TransLink, which raised $339 million in 2017. This regional property tax is a relatively small portion of total property taxes paid, and works out to $193 for a residential property valued at the regional average assessed value ($678,000) and just over $3,000 for a commercial property. In the absence of increased regional property taxation, individual Metro Vancouver municipalities could also raise their own property taxes to support the mobility of their own citizens. This may be more politically palatable, but this would likely lead to very uneven coverage across the region.

As a long-term objective, free public transit for all would be worth considering, particularly given the growing challenges of congestion and other costs that private car ownership imposes on society. Discounts for those who most need it could be an important step towards this goal, and would help foster a culture of transit use among youth that would carry forward in life (already, young people are much less likely to get a driver’s license than a decade ago).

Reducing fares for low-income people and youth would not cost much money, and would have a large benefit. While it is understandable that TransLink would want provincial funding to implement fair fares, the organization could make transportation more equitable on its own through some mix of the above options. While this would pose little difficulty in financial terms, it would greatly enhance the mobility of low-income households and youth, and contribute to a reduction in poverty in Metro Vancouver.

Topics: Municipalities, Poverty, inequality & welfare, Privatization, P3s & public services