It’s 2021: Time to get serious about BC’s carbon emissions

In December 2020, the BC government released its first Climate Change Accountability Report, the result of 2019 legislation aimed at improving the reporting and oversight of climate action in BC. The report lacks accountability in one important respect: it is not an independent assessment and reads like previous BC government reports on climate action that pat themselves on the back for a job well done. In this case while simultaneously announcing the delay of further action.

The new legislation was deemed necessary because of the province’s failure to implement measures that would put BC on a pathway to meet its legislated targets. While CleanBC (the province’s climate plan) is chock full of initiatives, many of which are important and positive, they nevertheless are not aggressive enough to achieve the province’s new 2030 target of 40% below 2007 emissions.

This post reviews how we got to this stage and what’s coming next, including a new commitment to net zero emissions by 2050 and a new federal climate plan calling for much higher carbon prices. Key findings:

- The new climate accountability report pushes back the timeline for tabling new measures to meet BC’s 2030 target to the end of 2021.

- CleanBC does not include any planning to meet BC’s 2040 and 2050 emissions targets.

- BC’s targets are incompatible with provincial plans for an LNG export industry.

- A more rigorous carbon budgeting approach is required to deliver emission reductions every year starting now.

BC’s 2008 Climate Action Plan

In late 2007, with great fanfare, the Gordon Campbell-led BC government passed the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act, which put into legislation a 33% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) or carbon emissions by 2020 (below 2007 levels), and 80% by 2050, with interim targets to follow. Legislating the targets, it was argued, meant they had to be taken seriously by future governments.

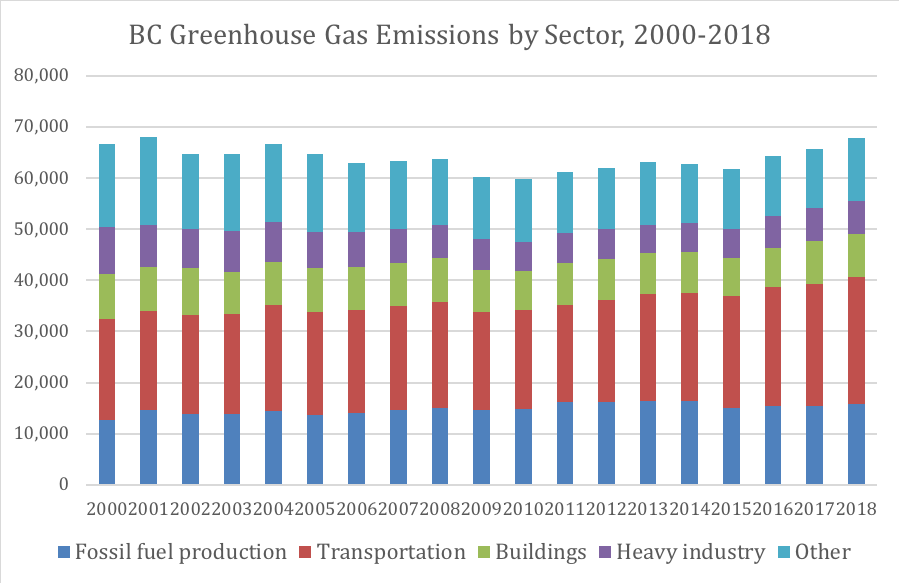

As of 2018 (the last year for which we have statistics), BC is nowhere close to meeting that 2020 target. Indeed, BC’s carbon emissions increased four years in a row, including a jump of 3% between 2017 and 2018 alone. Those 2018 emissions are 7% above the 2007 benchmark. This is sobering news to many who thought that BC was “bending the curve” on emissions.

So what happened? The Campbell government claimed that its 2008 Climate Action Plan would get the province 75% of the way to the 2020 target, then stopped trying to complete the task. Instead, starting in 2011 a new direction emerged under premier Christy Clark based on massive expansion of fracked gas development in the northeast combined with dreams of exporting that gas to Asia in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

In 2018 emissions from fossil fuel production (coal, oil and gas) were 8% higher than 2007 levels. About one-quarter (23%) of BC’s emissions stem from the extraction and processing of fossil fuels, most of which are exported. Consequently, any successful climate plan must reckon with reducing these emissions and that means winding down coal and gas production over the coming decades. Note that these figures do not count the carbon emissions from the eventual combustion of fossil fuels BC exports to other provinces and countries (extracted carbon); they only count the domestic emissions associated with getting fossil fuels out of the ground and out of province.

Transportation is another challenging area, accounting for more than one-third (37%) of BC’s total emissions in 2018. Emissions from ordinary cars (light duty vehicles) have dropped somewhat since 2007 while BC’s population has grown. That’s the good news. The bad news is that almost every other transportation sector has seen emissions grow, such as freight transportation (many large trucks support the gas industry, delivering water, sand and chemicals to fracking sites) and off-road emissions from pipelines, marine transport and railways.

Clean BC’s misleading claim

By the time a new BC government arrived in 2017, it was very clear that the province would miss its 2020 target by a country mile. The BC government’s 2018 CleanBC plan thus set a new target: a 40% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 (also relative to 2007 levels).

Like its predecessor in 2008, the government claimed that emissions reduction measures in CleanBC would get us most (75%) of the way to the legislated 2030 GHG target. This claim was politically successful as a factoid shaping the public debate, with all three political parties and a number of commentators repeating it during the 2020 election campaign. The claim held power because it was supposed to be the result of a sophisticated emissions modelling exercise.

Unfortunately, the 75% number was more fiction than fact, and even at face value, BC was an estimated six million tonnes short of its 2030 target.

Industrial emissions, in particular, were not modelled at all but were instead the product of “post modelling adjustments.” Much of the presumed reductions from industry is assumed to come from electrification of upstream gas production and reducing methane leakages (methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide). In this case there was no modelling. It was just assumed that the target 45% reduction by 2025 for methane would be met through introduction of best practices and technologies.

Other industrial emissions are also beyond the scope of the model, and there is little to point to in policy that would drive major emission reductions. The central policy plank in CleanBC is that incremental carbon taxes above $30 per tonne paid by industry would either: (a) be rebated to companies that meet certain performance standards for GHG intensity (to be developed); or (b) go into a fund to support technology development and adoption.

It was very clear that the province would miss its 2020 target by a country mile.

In other areas, the modelling for CleanBC went beyond what was in the actual plan. For example, it assumed that the zero-emission mandate for light duty vehicles also applied to heavy duty vehicles. The modelling also included proposed measures that had not been funded by the government.

Perhaps the biggest flaw in CleanBC is that it permits LNG development. Therefore, if BC is to meet its targets every other sector will have to do relatively more. LNG Canada, anticipated to start in 2025, will become the province’s largest point source emitter of GHGs the day it opens. Looking farther out, locked-in emissions from LNG Canada alone will make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for BC to meet its 2040 and 2050 targets of 60% and 80% emission reductions (below 2007 levels).

In the 2017 election campaign sectoral targets were promised in addition to the overall BC emission reduction target. At the end of 2020, a discussion paper was released seeking public comment on targets, but it really only starts the conversation about what targets should be developed. The current commitment is for sectoral targets to be published by March 2021.

2021 will be an important year for climate action in BC

When CleanBC was launched in late 2018, the government promised that additional measures to close the 2030 emissions gap would be tabled by the end of 2020. The new climate accountability report pushes that commitment to the end of 2021. And it states that previously announced CleanBC measures now get us only to somewhere between 56% and 72% of the 2030 target (the same caveats noted above still apply).

The BC government is now proposing a more stringent net zero target for 2050. This is in line with the federal government’s own net zero pledge and reflects that our targets need tightening in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. However, the CleanBC plan does not look past 2030 and how to meet the province’s targets for 2040 and 2050. And the “net” part of net zero will likely still permit carbon emissions in 2050 if they come alongside carbon capture and storage, tree planting and offset schemes.

Setting targets is one thing, action is another. The simple reality is that what BC needs is more ambitious action starting now and with actual reductions in actual emissions every year. We need to stop talking climate action out of one side of our mouths while promoting more fossil fuel production out of the other side (a problem shared by the feds).

A new federal climate plan, released in December 2020 (CCPA commentary here), proposes a major increase in carbon prices, rising to $170 per tonne by 2030 (about 40 cents per litre at the pump). This and other new federal measures will help the effort in BC, but BC also has an opportunity to rise to the top of the class by tabling new climate action measures.

The CleanBC plan does not look past 2030 and how to meet the province’s targets for 2040 and 2050.

A carbon budget approach would have a number of advantages over the current political game of setting distant future targets and then failing to meet them. Carbon budgeting would be more like the conventional way we do fiscal planning: a target is stated at the start of the year, along with actions on how it will be achieved (including credible investments that create jobs in green infrastructure), followed by routine monitoring and reporting.

Like the annual BC budget process, a carbon budget framework could set out rolling three-year plans and forecasts. Carbon budgets should be applied both to emissions released within BC’s borders (the standard way of measuring emissions) as well as for extracted carbon (the amount of fossil fuels removed from BC soil, the vast majority of which are combusted elsewhere). Planning within a carbon budgeting framework would thus entail a carbon test for major infrastructure projects.

The latest data show that we can no longer just get by on wishful thinking and good intentions. A more rigorous approach is needed to map out a schedule to bring fossil fuel production down from current levels to zero by 2050. This links to future decisions on new fossil fuel versus green infrastructure investments, jobs and training plans for workers, and a green industrial strategy for the province.

This post is part of the Corporate Mapping Project, a research and public engagement project investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry in Western Canada, led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (BC and Saskatchewan Offices) and Parkland Institute.