BC should eliminate the MSP. Here are two better options.

The MSP has been in the news a lot in recent months, and with good reason: it’s an unfair tax that needs to be eliminated.

The BC government announced some reforms to MSP in Budget 2016, in response to mounting pressure from grassroots organizations like the BC Health Coalition, concerned citizens and both opposition parties.

But the changes fail to address the fundamental problem with MSP: it’s a regressive tax, which means it takes up a much bigger share of income for lower-income families than higher-income families.

The way to fix that is to eliminate the MSP altogether. But how would we replace the $2.5 billion in revenue it brings each year? Read on. I’m going to walk you through two options, both of which involve creating a fairer tax system for all British Columbians. (All modelling is done with Statistics Canada’s Social Policy Simulation Database and Model. Fellow nerds should check out the technical appendix.)

MSP is unfair and unnecessary.

MSP is BC’s most regressive tax, meaning that it consumes a bigger share of income for lower-income people than for higher-income people.

Rates are set at a flat dollar amount by family size for all but the lowest-income families, who qualify for premium assistance. The amount is inconsequential for higher-income families but represents a significant expense for those with modest incomes. For example, a two-parent family with a combined income of $40,000 currently pays $1,800 per year, the same as a family making $400,000. That’s 4.5% of the first family’s income and only 0.45% of the second’s.

Premier Clark defends MSP as a necessary cost of public health care, but the reality is that all other Canadian provinces provide this care without charging unfair health premiums.

Adding insult to injury, many people with jobs that offer benefits – jobs that typically have higher than average wages – have their MSP premiums paid by their employers, while people in precarious jobs with low wages and no benefit plans are left having to pay themselves.

Premier Clark defends MSP as a necessary cost of public health care, but the reality is that all other Canadian provinces provide this care without charging unfair health premiums.

Ontario and Alberta used to have similarly structured health premiums but scrapped them as of 1990 and 2009, respectively. Instead of following suit, the BC government doubled down on MSP. Since 2001, MSP rates have more than doubled, rising from $432 to $900 per year for individuals and from $846 to $1,800 for families of three or more. Rates are going to increase by another 4% next January, as they have every year since 2010. The province now collects almost as much from MSP as it does from corporate income taxes (the ratio was closer to 1:2 in 2001).

These hikes to MSP happened at the same time as major income tax cuts that benefitted upper-income British Columbians the most. It’s ironic that a government so committed to tax cuts has felt so free to hike MSP rates, BC’s most regressive tax. The combined effect is a much less fair provincial tax system.

New research shows that if BC replaced MSP w/ more fair taxes most families would see savings. #nomoremsp #bcpoli https://t.co/QZmF0iexIw

— Iglika Ivanova (@IglikaIvanova) July 6, 2016

Contrary to popular perception, the MSP’s only connection to our public healthcare system is its clever name. MSP simply flows into general revenues and the amount it raises covers only 13% of what BC spends on health care.

There’s no reason we can’t replace the revenues collected from MSP with fairer taxes, so that we fund health care the same way we fund public schools, policing, environmental protection, and all the other public programs and services.

The MSP changes in BC Budget 2016 don’t fix the problem.

BC Budget 2016 announced that MSP rates will go up by 4% next year, but will be based on the number of adults in the family instead of on total family size. The new rules exempt children but increase the rate for adults living in couples. In practice, this will:

- increase rates for couples without children by $240 per year (5%)

- leave two-parent families largely unaffected, except for the 4% increase in rates which will cost $72 per year, and

- reduce rates for single-parent families, unless they are already covered by premium assistance.

Also as of January, more low-income earners will be eligible for reduced MSP rates.[1]

These reforms will provide welcome relief for some families but they do not eliminate the fundamental problem with MSP: this tax still takes up a much bigger share of income for lower-income families than higher-income families.[2]

We can replace MSP and increase tax fairness at the same time.

- Option 1: Small increases to personal income tax

- Option 2: Small increases to personal income tax + changes to business taxes

Income tax is the most progressive personal tax we currently have. It applies higher tax rates to those with higher incomes through a series of tax brackets.

If we use personal income tax to make up the lost MSP revenue, most British Columbians will come out ahead. We’ll pay a little more income tax, but savings on MSP would outweigh the costs for all but the highest-income families (see the next section for details).

Another option is to replace MSP with a combination of personal and business taxes. This is what Ontario did when it got rid of its health premium in 1990: slightly higher income tax replaced two thirds of the revenues and a new Employer Health Levy replaced the other third (see p.23 here). The levy, which is still in place today (now known as the Employer Health Tax), is a tax of up to 1.95% on total wages, salaries and other compensation paid by the business, with lower rates for smaller businesses.

The Ontario government argued at the time that a combination of personal and business taxes would be a fair reflection of the fact that both people and business benefit from public health care and have traditionally shared the costs. As is the case in BC, many Ontarians had their health premiums paid by their employers.

If BC replaced the MSP with income tax alone, it would result in considerable savings to businesses that currently cover MSP for their employees while these same employees would pay higher income tax without seeing any savings.[3] Workers would have an opportunity to negotiate for the employer’s savings to be passed on as wage increases, whether through collective bargaining or individual contract negotiations, but they might not always be successful. Instead, employer savings might go to shareholders in the form of higher profits or to consumers in lower prices.

This is why I think my second option makes more sense – to replace MSP with a combination of personal and business tax increases, roughly in proportion to the share of MSP currently paid by individuals and employers.

Unfortunately, we don’t know precisely what share of MSP is currently paid by individuals and what share is paid by employers. The closest approximation comes from Ministry of Health data on the number of British Columbians enrolled in MSP as part of a group (i.e., through their employers), released through a Freedom of Information request.[4]

The Ministry data reveals that almost one million British Columbians had MSP coverage through their employers in 2014. Including their spouses and dependents brings the number up to just under two million or 42% of the people covered by MSP that year. Notably, the share of British Columbians covered by employers has been on a steady decline since 2000, when it was just over 47%.

So if we assume employers pay around 40% of MSP premiums in the province, BC could replace 60% of MSP revenues through personal income taxes and the remaining 40% through a business payroll tax.

Of course, there are endless possible combinations of income tax changes that would raise the same amount of revenues as MSP. I picked two that not only generate sufficient revenues but also improve the overall fairness of the tax system, skewing increases towards higher income families.

Here’s how replacing MSP would work.

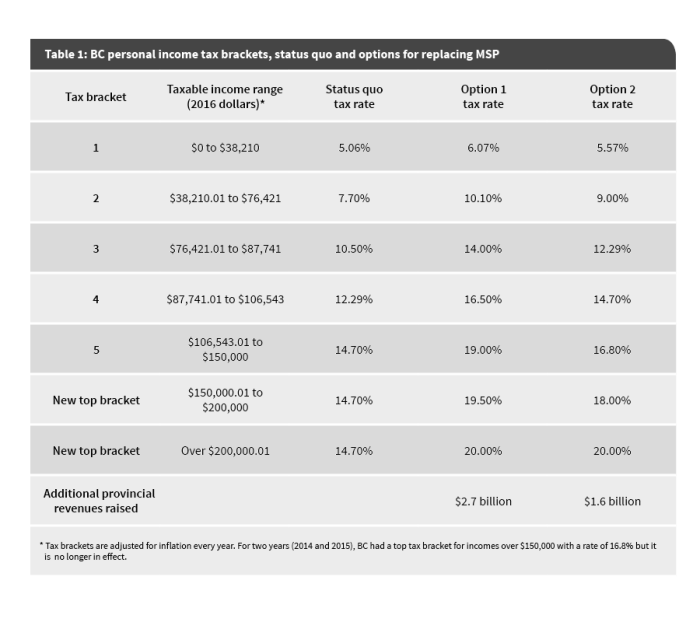

First let’s pause for a quick refresher on how our tax system is structured. BC has five income tax rates, which kick in at a series of set thresholds called tax brackets (as shown in Table 1). Once a person’s income hits the threshold for the next tax bracket, the higher rate applies only to the dollars above that threshold (not to their entire taxable income). Plus, various refundable and non-refundable tax credits reduce total income tax payable.

Although the bottom tax bracket technically starts at $0, no one pays taxes on their first $10,217 of income, known as the basic personal exemption. A rate of 5.06% applies to taxable income between $10,217 and $38,210. However, those with individual taxable income less than $31,600 are eligible for an additional tax credit, the BC tax reduction. As a result, people with taxable income of $20,000 or less pay no BC income tax and those with income between $20,000 and $31,600 pay less than 5.06% provincial income tax.

To replace MSP premiums with income tax revenues, I propose keeping the thresholds for existing tax brackets the same, and adding two new upper-income tax brackets in 2017 – one for taxable income between $150,000 and $200,000 and another for taxable income over $200,000. I also modelled slightly higher tax rates in each of the existing five tax brackets, with lower increases in the bottom two brackets, as shown in Table 1. I also boost the BC tax reduction amount so that British Columbians with taxable income less than $21,000 or so pay no income tax, and those with income under $30,000 pay slightly less than they currently do, making the system a little more generous.[5] Doing so ensures those who currently receive MSP premium assistance don’t end up paying more. The proposed top tax rate of 20% is lower than those in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec.

Who saves how much from eliminating MSP?

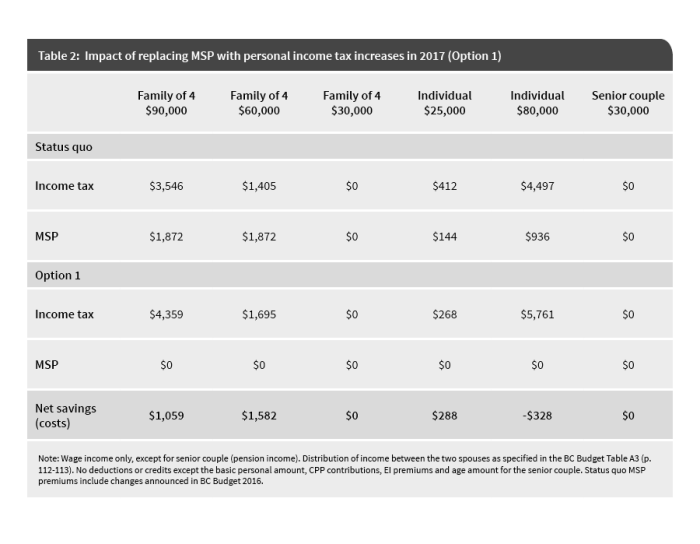

Table 2 shows examples of how different types of families would be affected by replacing MSP premiums with personal income tax increases in 2017.

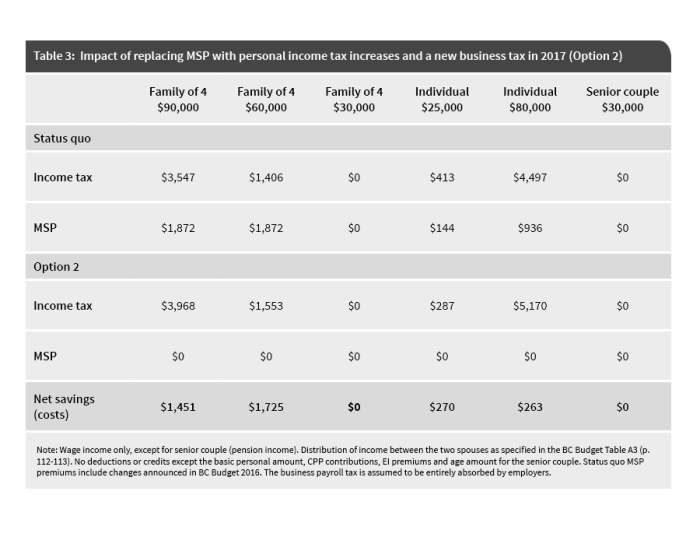

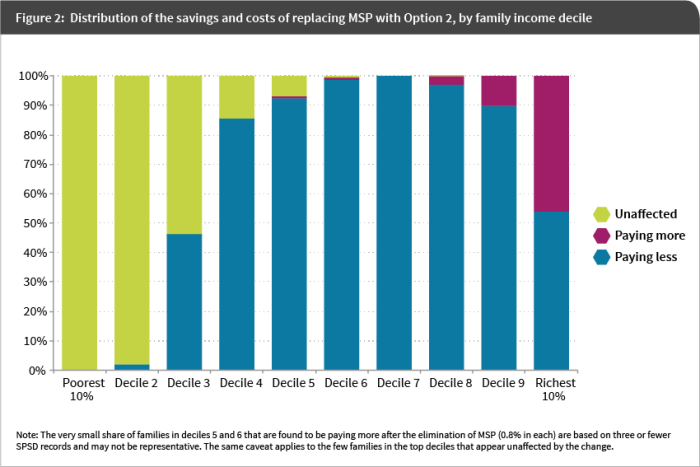

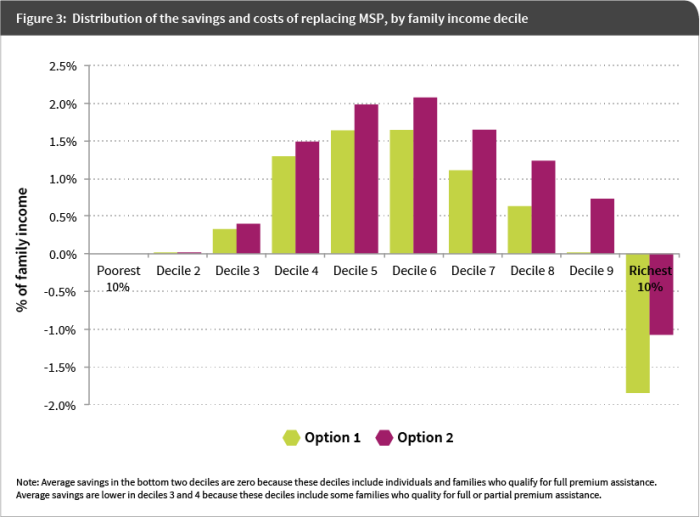

Option 2 features smaller income tax increases, which means more families benefit – 67% – and only 6% of families pay more. The remaining 27% of families would see their total tax bill unchanged.

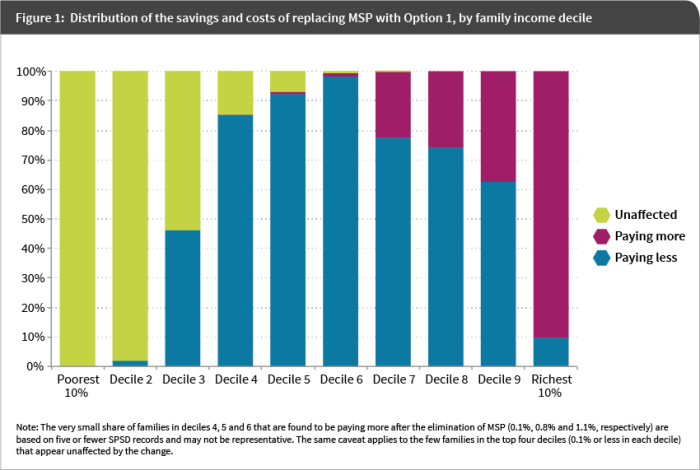

Families eligible for a reduced MSP rate will also get ahead, saving all or part of the premiums owed (decile 3 and some larger families in higher deciles). Families who are eligible for full premium assistance (those in the bottom two deciles) would be largely unaffected by the change.

Bottom line: eliminating MSP would benefit most British Columbians, especially if businesses pay their share too.

The elimination of MSP would benefit a majority of families, regardless of which tax reform option is chosen. Better off individuals and families would pay a little more income tax, but they will save the full amount of MSP premiums currently paid. This is why the net costs of a tax increase similar to what is modelled in Option 1 would be minimal for all but the richest 10% of families.

Option 2 would result in even higher savings for BC families, as some of the costs would be absorbed by businesses (the same share of MSP that businesses already pay, though the costs would be spread out more fairly across employers).

The results shown in Figure 1, 2 and 3 are based on the assumption that all individuals and families whose incomes are low enough to qualify for premium assistance actually receive it (i.e., 100% take-up rate). In reality, families have to submit an application for premium assistance and not all who qualify know about the program. A recent survey by the BC Seniors Advocate found that only 39% of seniors are aware the program exists. Those eligible families who are not accessing premium assistance would of course see significant savings from the elimination of MSP.

The elimination of MSP would benefit a majority of families, regardless of which tax reform option is chosen.

What about those who have their MSP premiums paid by their employer? The modelling doesn’t capture those, as Statistics Canada’s SPSD/M model assumes all premiums are paid by the individual or family.

We don’t have good statistics on the number of British Columbians who get their MSP premiums paid by their employers, the kinds of jobs they work in or the incomes they earn. We know that public sector employees typically have their MSP premiums covered and anecdotal evidence suggests that in the private sector, it’s usually the higher-wage and more secure jobs that come with benefits (including covering MSP premiums) while workers in precarious jobs with low wages and no benefit plans are left having to pay MSP premiums themselves.

While somebody who currently gets their MSP premiums covered by their employer would not personally see direct savings as a result of the elimination of MSP, the tax increase they’d experience under Option 1 is modest. And as noted above, those employees whose premiums are currently paid by their employer should seek to negotiate with their employer to ensure any employer savings are passed on in wage gains.

Employers who currently cover MSP premiums would see savings from the change.

If the portion of MSP premiums currently paid by the employers who offer benefits is replaced with a tax on all employers, then costs would be more fairly shared across businesses. This will result in net savings for the “good” employers and force employers who are currently free riding to pay their share. The business tax could be structured similar to the Ontario Employer Health Tax, based on gross wages and salaries (i.e., a payroll tax) with lower rates for smaller businesses that may be less able to afford it. The rate would depend on how the tax is structured but should be set to raise about $1.1 billion in 2017 (40% of MSP revenues).

What about the government workers employed in MSP collection?

Eliminating MSP would also streamline tax collection: instead of having to send separate monthly invoices for MSP premiums, process payments and follow up on late or missed payments, everything would be handled through the existing provincial income tax collection system. Collection of the business tax, if this option is selected, could be combined with WCB, BC’s only current payroll tax.

There are some government employees engaged in MSP collection who potentially stand to lose their jobs as a result of eliminating MSP. This isn’t a reason to avoid making this shift, but it calls for a strategy to help these employees transition to other work. All efforts should be made to retrain workers and employ them in areas of the BC public service that are currently understaffed.

BC already has the smallest public sector of all provinces and there are a number of areas of where similar skills are needed to improve public access to provincial benefits and services. One that comes to mind is at the Ministry for Social Development and Social Innovation call centres, where people who tried to reach the ministry about welfare benefits faced phone waiting times of 58 minutes on average in August 2015. Other government service centres could also benefit from a boost in staffing, such as those helping people with tenancy disputes or providing rental assistance.

Let’s do this.

BC is the only province in Canada to charge a head tax like MSP. Even our Premier says MSP “is antiquated. It is old, and the way people pay for it generally doesn’t make a whole ton of sense.”

It’s time to eliminate MSP and replace the revenues with fairer taxes.

It can be done. The public support is there. Will we see the elimination of MSP in one (or more) party platforms come next provincial election? Only time will tell.

[1] Single adults will pay nothing if they make less than $24,000 (up from the current $22,000) and will qualify for partial premium relief if they make less than $42,000 (up from the current $30,000). Couples, families with children and senior families will also see an increase in the income thresholds for receiving assistance – families can earn up to $2,000 more and pay no premiums and up to $12,000 more and still receive partial premium assistance (the exact thresholds vary by family composition, see p.52 of BC Budget 2016 for details). This is the first increase in income thresholds for premium assistance since 2010.

[2] For example, in 2017 a two-parent family of four with income of $40,000 will qualify for partial premium assistance and pay $1,152 for the year. This is less than the $1,800 they are paying now, but it’s 2.9% of their family income, still much more than the 0.47% of income a family making $400,000 will pay in 2017.

[3] MSP coverage by employers is considered a taxable benefit, so employees pay CPP and EI premiums on the amount, as well as federal and provincial income tax. If employees lose that part of their compensation without any wage increases, they’d still see some savings: they will save the taxes paid on the MSP premium amount. For example, CPP and EI premiums would add up to $131.98, and federal and provincial taxes would add another $375.52 in the bottom tax bracket (more if the employee is in a higher tax bracket).

[4] Inspired by David Schreck’s FOI request for 2014 data, I asked the Ministry of Health for data from 2000 onwards to see if group coverage trends have changed over the last 15 years.

[5] This is done by increasing the BC tax reduction amount to $630 in Option 1 and $550 in Option 2. The phase-out rate and the phase-out income threshold remain the same. In addition, both Option 1 and 2 also increase the BC non-refundable tax credit rate and the donations and gifts tax credit rate to match the tax rate in the bottom bracket (6.07% and 5.57% respectively).

Topics: Features, Provincial budget & finance, Taxes