Fighting poverty through tax credit reform

One way to fight extreme inequality is to have a progressive tax system.

We mostly think about this in the form of progressive income tax brackets, which are structured so that those who have higher incomes pay higher tax rates. Other taxes, however, like sales tax or the carbon tax, are not necessarily progressive in their distribution and to improve their fairness they have often, rightly, been accompanied by various exemptions and credits.

Providing tax exemptions and credits are alternative ways to deliver government programs and benefits through the tax system (as opposed to regular spending programs or various subsidies one has to apply for). Collectively, these are known as “tax expenditures” and they include tax exemptions from provincial sales tax (PST) for certain items such as food and residential energy as well as credits paid to households to address otherwise regressive outcomes such as the PST credit or the low-income carbon tax credit. There is currently a hodgepodge of these exemptions and credits in BC, each with its own design.

Tax expenditures add up to several billion dollars in foregone revenues from the public treasury in BC alone. There are even more when the federal level is taken into account. Yet, these costs are usually not as closely scrutinized as regular spending measures, which often result in tax expenditures not being as effective or as fair as they could be.

In this post I look more closely at BC’s tax expenditures and propose several reforms that would reduce poverty and create a more progressive tax and transfer system. What matters is the overall tilt of taxes, net of all exemptions and credits so that those who earn more pay more, not just in absolute dollars but more as a share of their income.

Providing tax exemptions and credits are alternative ways to deliver government programs and benefits through the tax system.

Reform of tax expenditures came up as a topic in the March 2018 final report of the Medical Services Plan (MSP) Task Force. The task force’s main work of examining how and when to replace MSP premiums as a source of provincial revenue was largely pre-empted when the BC government announced in its February 2018 budget the elimination of MSP premiums as of 2020, and partial replacement of those revenues through a new Employer Payroll Tax. In its final report, the task force shifted emphasis to other tax reform proposals to improve tax fairness in BC.

The task force’s most interesting recommendation was a to combine an enhanced PST credit, a reformed Home Owner Grant and the Low Income Climate Action Credit into a single income-tested transfer, which they call the Dogwood Benefit. The shift they propose is mostly revenue neutral, meaning no net cost to the Treasury with the exception of an additional $265 million that represents the government’s election promise of a renters’ rebate.

CCPA-BC has made similar recommendations over the years, in particular with regard to reforming the Home Owner Grant as well as enhancing the Climate Action Tax Credit. If anything, there is much more that could be done by a thorough review of these tax expenditures and below we consider further reforms as a contribution to a BC poverty reduction strategy, building upon the MSP task force recommendations.

Home Owner Grant

In the context of BC’s housing affordability crisis as well as tax fairness, reform of the Home Owner Grant (HOG) should be near the top of the priority list. All homeowners with a principal residence valued under $1.65 million currently receive a grant of $570 per year, with an additional $275 for seniors, veterans and people with disabilities or those living with them. There is another $200 for those living outside Metro Vancouver, the Fraser Valley and the Capital Regional District, which means that a large share of rural homeowners get more HOG than they pay in property tax. For residences above $1.65 million in assessed value the grant is phased out, but that threshold is increased each year “to ensure that the value of at least 91% of homes in BC are eligible.”

In 2018/19 the estimated cost to the Treasury of the HOG is $824 million in foregone revenues, a substantial sum. During the 2017 election campaign, the NDP promised to partially level this playing field by creating a “renters’ rebate” of $400 per year, at a cost to the Treasury of approximately $265 million annually. This item was missing from the plethora of housing measures announced in the February 2018 budget.

The MSP task force recommends eliminating the HOG in its current form, as it “largely benefits relatively high-income individuals and is limited to property owners, who are often wealthier.” In my previous housing report, I recommended turning the HOG into an income-tested benefit that would go to owners and renters alike. This would essentially be a transfer from high-income owners to low- to middle-income renters.

The task force proposes separate owner and renter benefits, each with a $750 annual base rate plus an additional $275 for people with disabilities or those living with them. The additional amounts for seniors and for rural areas, however, are eliminated. In their illustrative example, at $100,000 of household income the benefit would be gradually reduced and by $140-155,000 of income it is phased out entirely. In addition, the credit would be phased out for owners with properties valued at more than $1.65 million, similar to the current HOG. For renters, only one credit would be available per rental dwelling.

In the task force’s example, the homeowner credit would cost just under $700 million and the renter credit just over $400 million, for total housing transfers of $1.1 billion. Some 96% of renters would qualify for the credit and 77% of homeowners. Note that this includes new money. If we wanted to make the whole proposal revenue neutral, another option (not stated in the task force report) would be to eliminate tax exemptions from the property transfer tax, which together could fund the additional $265 million cost proposed by the task force. This includes exemptions for first-time homebuyers ($85 million in 2017/18 according to Budget 2018), newly built homes ($84 million) and property transfers between related individuals ($160 million). In the latter case, we would not necessarily recommend eliminating the full amount as some of this represents divorces or other particular situations.

Enhanced BC Sales Tax (PST) Credit

The MSP task force proposes to eliminate the sales tax exemption for non-alcoholic beverages, which are mostly sugary pop and juices (milk and non-carbonated water are still exempt). And, the task force recommendation would generate $120 million annually, which they propose would be used to enhance the PST credit to low-income families. If anything, public policy is moving further by contemplating higher taxes on sugary products due to their adverse health impacts.

The current PST credit costs $44 million per year and has a maximum value of a paltry $75 per year, which the task force notes “is insufficient to make any real impact on tax system progressivity by assisting low income households.” The task force proposal would increase the PST credit to a maximum of $220 per year.

But why stop there? The exemptions from PST are quite large and substantial benefits flow to households that do not need the break. According to the BC Budget, these include food ($1.3 billion, of which $120 million is for non-alcoholic beverages), residential energy ($209 million), prescription and non-prescription drugs ($242 million), children’s clothing and footwear ($47 million), books, magazines and newspapers ($45 million), specified school supplies ($31 million) and basic phone and cable ($56 million).

Altogether these exemptions total $2 billion. Changing the structure so that everyone pays full PST is technically regressive in distributional impact, but if that amount is fully transferred along the lines described above, the additional income to low- to middle-income households would be a highly progressive anti-poverty measure.

For PST tax increases, I estimate impacts for 2020 as follows, based on the Statistics Canada Survey of Household Spending. Set against the credit we can see that the net impact delivers more than $1,000 in net credits to the bottom quintile (20%), and there is still a positive net benefit in the middle quintile while the top quintile would pay an additional $1,366 in sales tax without receiving any credits.

| All quintiles | Lowest quintile | Second quintile | Third quintile | Fourth quintile | Highest quintile | |

| Total extra PST | $939 | $566 | $757 | $899 | $1,106 | $1,366 |

| Enhanced credit | $939 | $1,618 | $1,620 | $1,081 | $375 | |

| Net credit | $1,052 | $863 | $182 | -$731 | -$1,366 |

Climate Action Credit

The task force does not propose any reform of the Climate Action Tax Credit and simply rolls the existing means-tested credit into its proposed Dogwood Benefit. In its September 2017 mini-budget, the BC government announced an enhancement of the low-income credit from $115.50 to $135 per adult and $34.50 to $40 per child. The cost of this move was $40 million per year (as of April 1, 2018) and will bring the total value of the low-income carbon credit to $235 million annually.

While there is a clear benefit to low income households by increasing the credit, it falls short of the new government’s election promise to “increase the climate action rebate for low and middle income families, as the carbon tax increases, so that 80% of all households would receive the rebate.”

In previous work on carbon pricing, I have proposed that the low-income credit be modified to have higher base amounts and to reach higher up the income ladder. I did some modeling of the election commitment here such that (a) the bottom 50% get back more in new credits than they pay in new carbon tax (the $6 per tonne increase) on average; and (b) the bottom 80% receive credits. There are a number of ways this could be designed, but overall it means a larger share of carbon tax revenues be allocated to the credit.

Given rising gas costs and Hydro rates, lower-income households will increasingly experience the challenges of “energy poverty” [see our report here]. In light of this reality, a strong case can be made for boosting the low-income carbon tax credit as a simple means of offsetting the rising energy costs facing low and modest-income families.

Anti-poverty impact of reforming tax expenditures

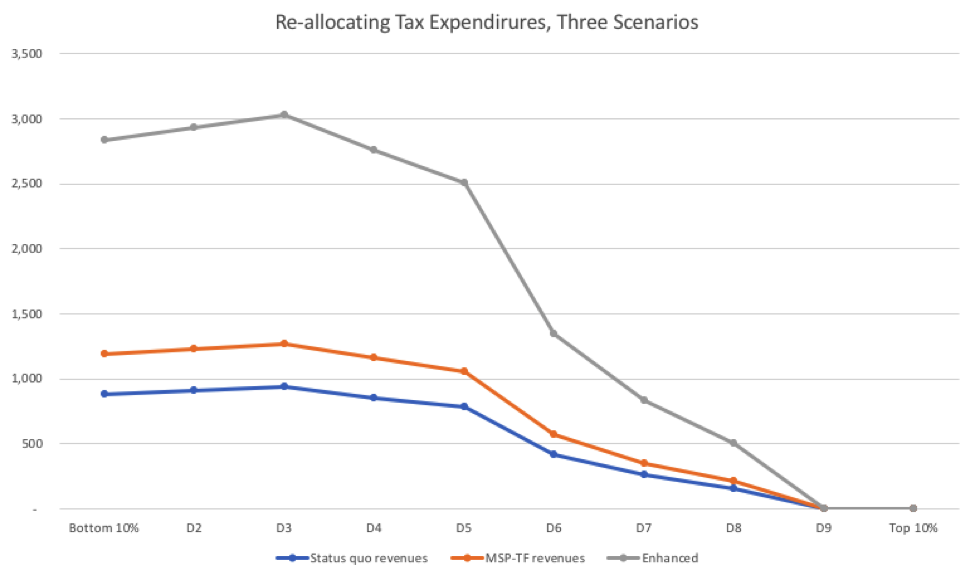

In the Figure below I show three increasingly progressive versions of tax expenditure reform. All are based on a formula where a maximum credit goes to the bottom of the distribution, which then gets phased out so that the bottom 80% of households get some amount of credit and the top 20% do not get anything. Note that this analysis uses households not individuals. Because there are more individuals that multi-person households in the bottom quintile the average credit is somewhat less than the next quintile. These are gross amounts and do not count additional sales taxes or carbon taxes paid.

The lower line shows the status quo forgone revenues for the HOG, carbon credit and PST credit (at estimated 2020 amounts), but those amounts have been reallocated to households along the lines stated above. It is revenue neutral, meaning there is no additional cost to the BC government.

The middle line somewhat enhances the credit; it shows the impact of the MSP Task Force proposals (Dogwood Benefit) and includes taxing non-alcoholic beverages and adding that to the PST credit, plus $265 million promised during the election campaign for a renters’ rebate.

According to the modelling undertaken for the task force, the proposed Dogwood Benefit for a single individual would provide a maximum of $1,100 per year, $1,400 for a one-income couple and $1,500 for a two-income family of four. These amounts are more than the current maximums of about $200, $400 and $500 respectively.

Going back to the Figure, the top line shows a more aggressive approach to reallocating and expanding tax expenditures. It would build on the task force proposals above by:

(a) doubling the total amount of the carbon credit to $470 million, funded out of additional carbon tax revenues;

(b) eliminating other tax expenditures related to housing for first-time homebuyers, new homes and inter-family transfers to pay for the additional $265 million housing amount, for a total impact of $1.1 billion (includes reallocation of HOG); and

(c) eliminating most other PST tax expenditures for a total impact of $2 billion.

This proposal is completely revenue-neutral and would provide gross credits of almost $3,000 per household for the bottom 30% of the income distribution, then phase out gradually. A household in the eighth decile would still receive a combined credit of $504 on average although it would face higher PST on purchases (see table above).

There are many possible design permutations of these ideas, but a key point to make a strong anti-poverty impact would be to reallocate existing tax expenditures away from households that do not need them to households that do. In addition, this exercise need not be revenue neutral: new revenues from progressive taxation could be used to boost expenditures and increase the anti-poverty impact.

Such a shift in thinking could also form the basis of a basic income concept in BC, another topic under consideration by the provincial government and part of the 2017 Confidence and Supply Agreement between the NDP and Green Party.

Reallocating tax expenditures from households that do not need them to households that do would have a strong anti-poverty impact.

One challenge of basic income is that it is costly. The allocation I have chosen reflects a Canadian compromise between universality and affordability—this is how the federal government already distributes child benefits and old age pensions. In essence, all these credits function as a form of basic income—the only qualification for receipt of the benefit is one’s income level.

A further challenge is that not everyone files taxes and, therefore, may miss out on benefits. A more comprehensive system would create strong incentives for filing, but additional measures would need to be considered so that, for example, homeless people can benefit. Reforms to ensure that credits go to households on a regular basis when they need it should be considered as opposed to benefits based on the previous year’s taxable income.

All told, an integrated and enhanced credit such as this could represent a very helpful piece of a comprehensive poverty reduction plan. It can effectively transfer income to lower income people—both those on welfare and the working poor, those with children and without, the young and the old.

Topics: Economy, Provincial budget & finance, Taxes