Firehose of corporate cash or financing our democracy together? A no-brainer

A long-overdue and badly-needed overhaul of BC’s election finance rules was introduced by the provincial government last week. Media headlines mostly focused on the decision to include public funding for political parties, questioning whether it is an appropriate use of taxpayer dollars and whether the governing NDP has reversed itself on this issue.

But this focus obscures a much more important question: what is the most democratic way to finance our political system—and how do the new rules stack up?

Big money vs our money

As we’ve seen in BC, the alternative to financing our democratic process together, through public funding, is big money. Letting corporations, unions (though in practice it is corporations that contribute the lion’s share of cash) and the wealthy pick winners in the competition for donations is a profoundly undemocratic way to do politics.

First, allowing big money in politics violates the fundamental principle of one-person-one-vote—the idea that democracy rests in the hands of citizens who each have an equal say in determining how we will govern ourselves. Big money distorts elections, giving the rich a megaphone that drowns out the voices of citizens and biasing the political agenda in favour of already-powerful interests. It’s also part and parcel of the expansion of rights for corporations as “legal persons”.

Second, big money corrupts. As we learned during the lead-up to the last provincial election, the big money free-for-all in BC has seen lobbyists making hefty donations to secure access to government decision-makers, and even donating illegally on behalf of their corporate employers and clients.

Our research with the Corporate Mapping Project uncovered not only that major Calgary-based fossil fuel corporations are among the most generous donors to BC political parties (primarily the BC Liberals), they are also among the most active lobbyists, routinely bending the ear of cabinet ministers and senior government officials.

Last week we revealed that many of those same oil and gas corporations were invited by the previous government to shape the province’s Climate “Leadership” Plan in closed-door meetings the public was told nothing about (until we obtained the evidence via repeated Freedom of Information requests). Those meetings took place in Calgary, and were jointly organized by the BC government and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, the country’s most powerful oil and gas lobby group.

As UBC political scientist Max Cameron says, such institutional corruption “is a betrayal of the public purpose of democratic institutions, and it weakens trust in government. A more compelling reason to get big money out of politics would be hard to find.”

Allowing big money in politics violates the fundamental principle of one-person-one-vote.

The ban on corporate and union donations is a vital step forward in reducing the undue influence of corporations and the wealthy. The decision to prohibit parties from using corporate and union donations already in the bank during future elections is also a positive move.

With new donation limits in place, the flow of cash to political parties and candidates will be substantially curtailed. As we argued in an earlier post, reducing the amount of money sloshing around our political system is important. But elections cost money and our democratic process needs funds if those running for office are going to effectively develop and communicate ideas for the future of our communities and province. Also, we must ensure that anyone can run for office, not just the wealthy.

The legislation introduced this week uses a combination of methods to fund the political process. Individual donations will continue to be allowed, but capped at a maximum of $1,200 per year, and those donations will continue to be eligible for BC’s political contributions tax credit. In addition, for the next five years, political parties will receive a per-vote allocation of public funding (described as transition funding in the wake of the ban on corporate and union donations). Finally, following a current similar federal practice, candidates will be reimbursed for up to 50% of their election expenses.

The per-vote funding will cost about $16 million over the next four years. Interestingly, $16 million over four years is almost the exact same cost as the public subsidy system that has been in place for many years through the political contributions tax credit, but that is much less fair than the proposed per-vote option. The reimbursement of election expenses will cost about $11 million per election. So in total, about $26 million in new costs over four years. For context, on an annual basis, that’s 0.0125% of the current BC Budget.

A special committee will review whether per-vote funding should continue after 2022. This is a good move since there are in fact even more democratic ways to fund our political process. The tax credit should be reviewed too because like corporate and union donations it runs counter to the principle of one-person-one-vote.

Who’s got an extra $1,200 kicking around?

How many British Columbians have $1,200 per year to give to a political party? Most of us struggle to contribute to an RRSP and with the current affordability crisis, the maximum contribution limit will remain an option primarily for the well-heeled.

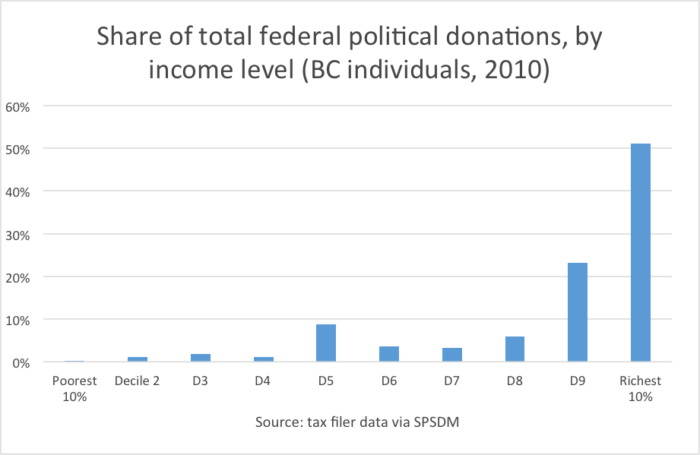

The pattern of federal political donations offers a helpful window on the likely makeup of individual donations in BC under a high cap like the one the government has introduced.

Using tax filer data, we can see the breakdown of federal donations by income level. Keep in mind that the federal government banned corporate and union donations over a decade ago and capped individual donations at a high level.

The data used here are from 2010 when the annual cap on individual donations was $1,100 per party, plus another $1,100 for candidates and constituency associations. (The Conservative government later raised the limit to $1,550 in each category).

The picture is stark: more than half of all donated funds come from the richest 10% of income earners and more than three quarters comes from the top 20%. In sharp contrast, the bottom 40% of earners is barely represented.

As a result, the political donations tax credit is distributed in much the same way: the overwhelming majority of dollars flow into the pockets of the affluent. Almost three quarters of the credits go to the top 20% of income earners.

There’s a clear lesson for BC here. Under a $1,200 limit, large individual donations will likely continue to swamp any $20, $50 or $100 donations. This means our political parties will have the incentive to focus more time and attention on affluent donors than on British Columbians with middle and lower incomes. An additional concern is that some corporations could seek to end-run the new rules by encouraging executives and their spouses to each donate the $1,200 limit while finding creative ways to reimburse them (such funnelling has occurred in other jurisdictions).

The maximum contribution limit will remain an option primarily for the well-heeled.

Luckily, adjusting the proposed cap on individual donations could be done with the simplest of amendments to the just-tabled legislation. The Attorney General has said that this legislation aims to make BC a leader in campaign finance regulations. We could do that by matching—or moving much closer to—Québec’s $100 limit on individual donations. It’s a matter of knocking a zero off the cap already proposed.

Political finance models to deepen our democracy

So what is the fairest way to fund our democratic system? The government has proposed, on a temporary basis, per-vote funding. This is certainly a major improvement over the big money free-for-all, but it has some problems.

First, the per-vote approach locks in public funding between elections, whereas voter preferences may change substantially over a government’s four-year term. Second, it has a status quo bias compared to other public funding models: political challengers are disadvantaged relative to incumbent governments and upstarts relative to established parties. Finally, per-vote funding binds a person’s vote with the allocation of money when citizens may want to separate these (e.g. by voting strategically during a particular election, but wanting to give a funding boost to a different party they really like best).

Consider these other innovative options:

Matching small donations. Under a matching system, small donations up to a certain amount (for example $25) are matched with public funding. Under New York City’s innovative system, donations are matched at a 6-to-1 ratio. So, a $10 donation from an individual is worth $70 to the party or candidate, leading them to value and pursue these types of donations.

This model has the advantage of motivating parties to seek the support and engagement of average citizens between elections, especially if combined with a low limit on individual donations.

The New York system has successfully increased both the total number of small donors and the proportion of small donations. It has also led to a shift in the demographic profile of donors to be more representative of the population.

Matching small donations means amplifying the voices of those with limited means who are too often shut out of the political process. Think back to the energy behind Bernie Sanders’ presidential nomination campaign last year and imagine if we built incentives for that kind of bottom-up political engagement into BC’s campaign finance system. The ratio of matching public funds and limits on individual contributions to be matched could be tailored to our provincial context.

Under a $1,200 limit, large individual donations will likely continue to swamp any $20, $50 or $100 donations.

Universal citizens’ voucher. Another option is to empower citizens to control the flow of public funding even more directly. A voucher system could be rolled into the elections section of an income tax return. Then, you could choose to direct your voucher amount (say $10 or $20 per year) to a party or withhold it if you’re dissatisfied with all the options available. Alternatively, vouchers could be sent by mail like in the voucher system Seattle is implementing this year.

This approach would put all citizens on equal footing in their ability to fund the political process, but without the drawbacks of the per-vote funding model. And if it’s already on your tax form or arriving in your mailbox, it would likely encourage more widespread participation than even a matching system could muster.

With either the matching small donations or voucher systems, total public funding could be capped. For example, the $16 million per election cycle that the political donations tax credit currently costs could be replaced by either of these options.

Free public airtime. We could also reduce the cost of election campaigns by mandating free public airtime for candidates on both private and public broadcast media. The airwaves are a publicly-owned resource, after all. Why should so much of our money (whether private donations or public funding) flow to media companies as advertising revenue?

Making the ban on big money airtight

The legislation introduced last week includes a host of other changes from clamping down on pay-to-play fundraisers (where donors pay big bucks to rub shoulders with party leaders or others in positions of power) to restricting who can lend money to parties and candidates.

Details like these are important. In the words of US Supreme Court Justices O’Connor and Stevens, “money, like water, will always find an outlet.”

This is why we also see new restrictions on “third party” advertising being introduced. With the ban on corporate and union donations, big money is likely to flow to political action groups like the “Future Prosperity for BC” and “Concerned Citizens for BC”—both of which were set up and funded by corporate interests in the lead up to the 2017 BC provincial election.

However, given there are serious problems with how BC’s existing third party advertising rules were designed, we’re holding judgment on the proposed amendments until we’ve had a chance to study them further.

**

Stepping back from the details, one thing is clear: the ban on big money is good news for BC. Given the choice between a fire hose of corporate cash and funding elections using our pooled tax dollars, we’ll take the latter option any day of the week.

Topics: Economy, Election commentary, Features, Transparency & accountability