Fixing the carbon tax: A closer look at the BC NDP’s climate plan

The BC NDP unveiled its climate plan in early February, and its key plank is to increase the BC carbon tax from its current $30 per tonne to $50 per tonne by 2022, in line with the new federal floor price on carbon.

The carbon tax increase under the BC NDP plan would be phased in a tad more quickly than the federal plan with rates of $36 per tonne in 2020 and $43 in 2021 compared to the federal floor prices of $30 and $40 respectively.

A key lesson of the BC experience with the carbon tax is that how revenues are used is central to whether the tax is effective and fair. The current carbon tax is supposed to be “revenue neutral,” meaning all revenues raised flow back out in the form of various corporate and personal tax cuts and credits. In truth, the BC carbon tax is not revenue-neutral, but actually revenue-negative; the regime as a whole pays out much more than it takes in as carbon tax revenue. Corporate tax cuts account for about 2/3 of carbon tax revenues.

Of particular interest from an equity perspective is the Low Income Credit. On its own, a carbon tax is regressive – meaning households with lower incomes pay a higher share of their income to the tax. The Low Income Credit helps to reduce the regressive impact. In its early days, the credit was sufficient to offset the average carbon tax paid by a low-income household. But as the carbon tax was increased, the credit was not adjusted accordingly, making the overall carbon tax and revenue recycling regime regressive.

A key lesson of the BC experience with the carbon tax is that how revenues are used is central to whether the tax is effective and fair.

Currently, households with incomes less than $33,326 for individuals and $38,880 for families get the full credit, worth $115.50 per adult and $34.50 per child. The value of the credit phases out very quickly above these income thresholds, and disappears entirely by $40,000 of individual income (for families it depends on the mix of adults and children).

The NDP’s proposed increase in the carbon tax will be revenue-neutral for 2020, with new revenues going to fund an enhanced carbon credit (called a “climate action rebate cheque”). While 80% of households would be eligible, it is not clear how the credit would be structured. For example, the same amount could go to all eligible individuals (sometimes called a “dividend”), or there could be a maximum amount up to a certain income threshold, after which it would be steadily phased out (similar to the current Low Income Credit).

For 2021 and 2022 the NDP would (rightly) break with revenue-neutrality, and use some of the new incremental revenue to support climate actions like increased public transit, energy efficiency retrofits and other clean technology.

The NDP’s proposed $6-per-tonne increase in 2020 would yield incremental revenue of approximately $238 million (for simplicity assuming that 2020 emissions are the same as 2007 levels). Averaged across all households, this is a carbon tax increase of $112 per year with high-income households paying more due to their greater consumption and larger family size on average.

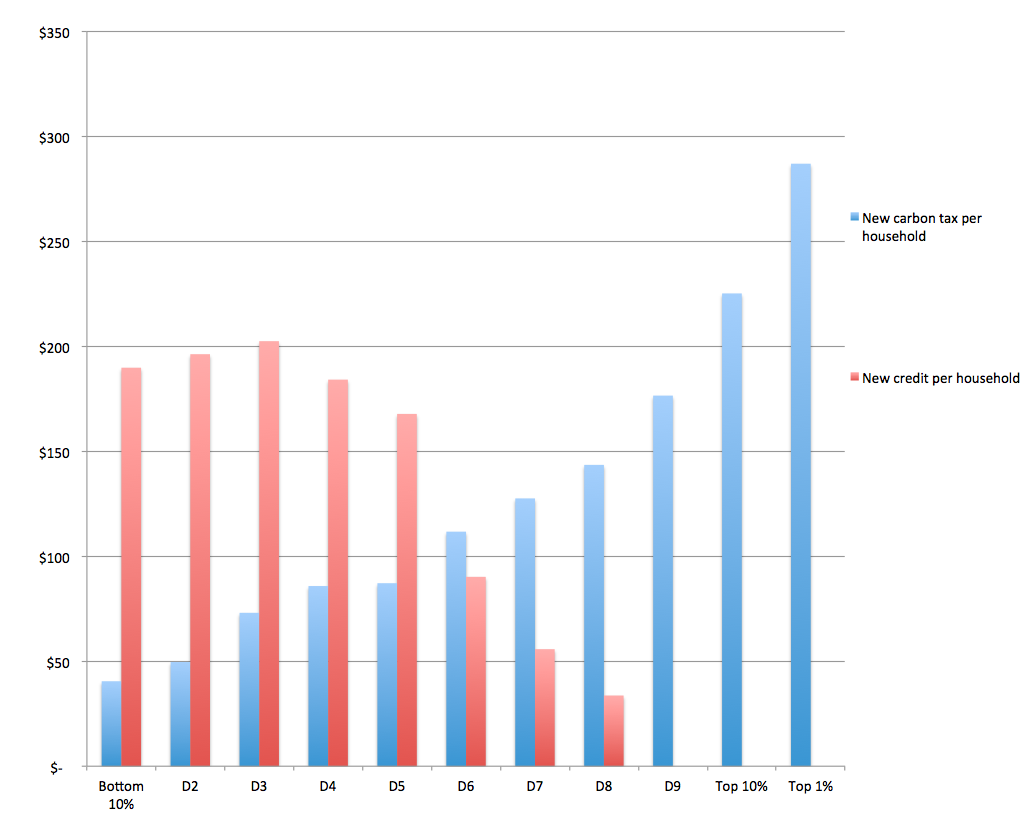

The Figure below is illustrative of what the credit could look like, although not necessarily what the NDP in government would actually implement. It models the new carbon tax(blue bars) and new credits (red bars) for 2020 by income group (deciles, or 10% groupings ranked by income, plus the top 1%). Average carbon taxes paid include all direct taxes (on motor fuel and home heating paid by households) and indirect taxes (those paid by businesses and passed on to consumers). This may overstate the carbon tax paid by households to the extent that a portion of those indirect taxes is passed on through exports.

On the credit side, there are many possible ways to design it. I chose to allocate all of the carbon tax revenue within the bottom 80% of households, such that (a) the bottom 50% get back more in new credits than they pay in new carbon tax (the $6 per tonne increase) on average; and (b) the bottom 20% get back more in total credits on average than they would pay in total carbon tax ($36 per tonne after the increase).

Figure: Average new carbon tax and carbon credit by decile, 2020

One interpretive note is that we are looking at households, not individuals, and the bottom 10% includes more individuals, so the average credit is lower per household. That is why the average credit increases up to the third decile before dropping back down.

It is entirely possible to proceed with annual increases to the carbon tax, and structure it in a way that the bottom half of BC households are better off.

How this would look in 2021 and 2022 depends on what the NDP does with revenues. For example, if all revenues in 2021 were to go to the carbon credit, the distributional impact could look much the same as the Figure (with all amounts slightly more than double). But new revenues are also intended to support new expenditures on transit, retrofits, and so forth.

Ideally, carbon tax revenues would support both increased expenditures and an enhanced credit. In this way the carbon tax would be the most effective and fair: raising the cost of emitting carbon, compensating for regressive tax impacts, and funding complementary climate action initiatives.

What is clear is that it is entirely possible to proceed with annual increases to the carbon tax, and structure it in a way that the bottom half of BC households are better off (with more money in their pockets). That’s good news for tax fairness even as we move forward on climate action.

Topics: Climate change & energy policy, Environment, resources & sustainability, Provincial budget & finance, Taxes