BC’s relief measures for people on income assistance are welcome but more is needed

On April 2, the BC government announced emergency financial support for some of the most vulnerable British Columbians: an extra $300 per month for people receiving income and disability assistance and some very low income seniors, for three months. This necessary and welcome measure can’t come fast enough.

BC is now only the second Canadian province to extend COVID-19 financial relief measures to people on income and disability assistance, after Nova Scotia launched a paltry $50/mo supplement. It’s telling that people receiving these benefits have been largely forgotten in this crisis so far, as they are hardly top of mind during normal times as well.

A bit of background: Income and disability assistance, also referred to as welfare, are the programs of last resort for people who find themselves without work, or who are unable to work because of a disability, illness or caregiving responsibilities. Income assistance falls under provincial jurisdiction, unlike employment insurance (EI) which is a federal program. In BC, there are two streams of benefits: temporary income assistance (for people who are considered employable) and disability assistance. Both are extremely difficult to access, requiring people to exhaust virtually all their savings before they can even apply. In nearly all provinces, income and disability rates leave recipients with incomes far below the poverty line.

The good news

The good news is that the $300/mo emergency crisis supplement is automatic and will not require a special application.

Also welcome news is that income assistance recipients who qualify for the Canada Emergency Relief Benefit (CERB) or regular EI will not have that money clawed back. A small minority of welfare recipients will qualify for the CERB because they have been able to earn some income through paid work (provincial earnings exemptions allow those receiving income assistance who are able to work part-time or occasional hours to keep some of those wages). The CERB is available to people who have lost income due to COVID-19 provided they earned a minimum of $5,000 in 2019. An estimated 10,000 BC households with disabilities and 1,000 households on temporary assistance will qualify — and for them it means they will be able to escape poverty for a few months.

This is in contrast to the usual policy of clawing back all EI benefits. Even though a certain amount of earnings are allowed on welfare, there is no corresponding exemption when a job loss means these earnings are replaced with EI benefits. Instead, EI is unfairly clawed back dollar-for-dollar from monthly cheques.

The BC government is also dropping the work-search requirement during the pandemic, as we called for previously. Typically, welfare payments are contingent on the recipient being able to demonstrate that they actively looked for work or engaged in approved training programs (this requirement does not apply to disability assistance).

Normally disability assistance recipients receive a $52/mo transportation supplement which they have a choice to get in cash or as a transit pass. Those who opted for the transit pass will receive the $52 cash payment for as long as bus fares are suspended in BC.

The not-so-good news

The emergency support payments will start in three weeks, on April 22 when the initial $300 is automatically applied to the next regular benefits payment. That means we are asking people in deep poverty who have few reserves to begin with to absorb the extra costs of living during the pandemic in the meantime. This long delay could have been avoided if the income assistance supports were announced a little earlier and paid with the end of March cheque as was done in Nova Scotia (though with a much smaller supplement amount).

Fortunately, the federal government has been able to expedite its one-time GST credit top-up payment to April 9, providing some desperately needed funds in the meantime. Income assistance recipients who filed their taxes for 2018 will qualify for a one-time extra benefit of $290 for a single employable person and just over $700 for a single parent with one child (slightly more for families with more children), which will not be clawed back.

The other federal and provincial emergency benefit top-ups that have been announced (via Canada Child Benefits and the BC Climate Action Tax Credit, which are also not clawed back from welfare) are not expected to be disbursed until May.

Also troubling is the discrepancy between what those who have been able to work enough part-time hours to qualify for the CERB can take home in emergency support (up to $8000 over four months), and the amount available for those who cannot work due to complex health conditions and therefore do not qualify for the CERB ($900 over three months).

Note that income assistance recipients will not be eligible for the provincial rent supplement of up to $500 per month, or the one-time $1,000 BC Emergency Benefit for Workers, even if they worked enough last year to qualify for the CERB.

BC income assistance recipients remain in deep poverty

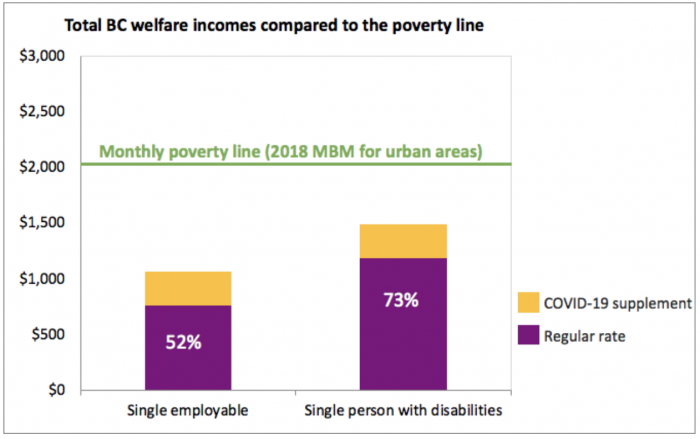

The monthly assistance rate for a single person considered employable is $760 and for these people a $300 crisis supplement represents a very significant increase. However, even with this temporary increase, the welfare income for a single person only amounts to half of the poverty line (as measured by Statistics Canada’s Market Basket Measure, adopted by the federal government as Canada’s official poverty line). The monthly poverty line for 2018 is around $2,000/mo for a single person in large BC cities with populations over 100,000 (and between $1,730 and $1,785 for smaller towns and rural areas). (Statistics Canada recently released a revised estimate of the MBM for 2018 for those who want more detail.)

People with disabilities receive a slightly higher benefit of $1,183/mo but they also face extra costs due to their disability. Figure 1 shows that even with the crisis supplement they will continue having to live at least $500 below the poverty line every month and remain in deep poverty.

These pitifully low welfare rates force many to live in sub-standard housing or to become homeless if they’re unable to get a subsidized housing unit (and waitlists for those are very long). Even SROs are too expensive for many welfare recipients: the average SRO rent in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside was $663/mo in 2018 according to the latest Carnegie Community Action Project housing report.

Low rates also force people to spend much of their time meeting their basic needs, for example by lining up for free food and relying on the now-closed public libraries and community centres to access the internet or find out what is going on in the community. Many people on social assistance can’t afford access to the internet or television to keep informed about the latest public health advice and developments in the pandemic, or access to government services that are increasingly provided online. With many community services closed or operating with reduced capacity during the pandemic, hunger and social isolation looms as a real problem for some of the most vulnerable British Columbians.

We have previously called on the Province to immediately and permanently raise welfare rates to at least 75% of the poverty line, and for a medium-term plan to bring welfare rates the rest of the way up to the poverty line to ensure people who have fallen on hard times or are unable to work due to illness or disability can live with dignity. The Canada Emergency Relief Benefit (CERB) similarly points to a standard that Canadians consider the bare minimum needed to live on: $2000/mo, which is remarkably close to the 2018 MBM for urban areas. Why are people on provincial income and disability assistance forced to live on much less?

Reality-check on “temporary” income assistance

In BC, over 206,000 people received income assistance in February or about 4% of the provincial population. The majority of these people (64%) received disability assistance, a quarter (26%) received temporary assistance in the “expected to work” category, and one in ten (10%) were receiving temporary assistance but not expected to be able to work (for example, due to being the sole caregiver of young children). The temporary assistance recipients include 23,000 families with children, the vast majority single-parent families. Another 10,000 families with children live on disability assistance.

The only way many welfare recipients can make ends meet is by supplementing their income with formal or informal work. However, much of this has likely dried up with the pandemic and the vast majority of working social assistance recipients would not qualify for the federal COVID-19 worker supports because they earned less than $5,000 last year. Without these lifeline sources of income, welfare recipients will be forced to try to survive on the pitifully low regular assistance rates.

According to Ministry data, the median length of time on temporary assistance was 10 months last year, which means that half of recipients left income assistance sooner but half needed benefits for more than 10 months. This is a very long time to be living on such vastly inadequate incomes. People with disabilities stay on assistance much longer, frequently for the rest of their lives. And with the economic disruption we are seeing with COVID-19, it’s likely that even temporary assistance will be required for longer than usual.

More British Columbians will likely need income assistance during the pandemic

We should expect to see a surge in welfare applications over the next few months. About a third of unemployed Canadians won’t qualify for the federal relief benefits and some of those will have to turn to provincial social assistance. BC should be prepared to process these new applications quickly.

The current application process is burdensome due to a number of barriers that discourage applications or delay support to people who find themselves in crisis. There is also a lot of stigma attached to applying for welfare. Although some very positive changes to several of these rules were made in BC Budget 2019, the asset limits remain low for those on temporary assistance forcing people to exhaust most of their savings before receiving assistance even for a month or two (which often means they have to leave their housing, can’t afford a phone or a data plan, etc).

Waiving asset limits for the duration of the pandemic and streamlining the application would make it possible for people in need to receive support faster during this challenging time and cushion the longer-term human and economic costs of the pandemic. In the medium term, an overhaul of the application process, end of unfair clawbacks and higher asset limits should be considered to ensure that all British Columbians who find themselves in crisis can receive income support without being forced into even deeper financial insecurity once life goes back to normal.

In sum, our recommendations for immediate further action are to:

- Permanently raise income assistance rates to at least 75% of the poverty line.

- Waive asset limits for the duration of the pandemic.

- Streamline the application process.

Topics: COVID-19, Economy, Poverty, inequality & welfare