The Racism behind Japanese Canadian Internment Can’t Be Forgotten

When John Horgan talked about BC’s historic racism, he failed to mention Japanese Canadians. Here’s why it matters.

Premier John Horgan began a media conference on June 3 with a statement about racism and the “blemishes” on BC’s history.

Horgan mentioned the head tax used to restrict immigration from China and the Komagata Maru incident that highlighted Canada’s discriminatory policies around immigrants from India.

But he failed to mention Japanese Canadians or the central role of the BC government in uprooting, incarcerating and exiling 22,000 Japanese Canadians between 1941 and 1949, stripping them of their homes, possessions and businesses.

Canadians have already deemed this episode, initiated and carried out by the province together with the federal government, one of the most blatant examples of state-initiated racism in the history of Canada.

Horgan’s omission is puzzling when his government is currently in reparation discussions with the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) based on a brief (partially funded by the BC government) submitted last November. Those recommendations included the creation of an independent body to combat racism.

BC’s conduct is no secret. It was recently highlighted in the video Swimming Upstream and a six-part series in the Victoria Times Colonist.

BC governments and officials played a major role in the incarceration and dispossession of Japanese Canadians, and in other racist actions over the years.

The BC legislature passed 170 anti-Asian laws from 1895-1950 that seriously impacted the Japanese Canadian community.

In 1942, BC premier John Hart, along with his attorney general Royal Maitland, a notorious racist who deemed Japanese Canadians “a menace to Canada” even after the war, were among the first to go to Ottawa to demand that Japanese Canadians be removed from their homes and forcibly relocated to the B.C. interior.

Provincial minister George S. Pearson was sent to Ottawa in January 1942 to demand Japanese Canadians be uprooted. There, he and the others from BC stunned the vice-chief of the army with his racist rage, according to Maurice Pope in his autobiography Soldiers and Politicians. Many in the federal government didn’t buy the BC government’s claims that Japanese Canadian were spies, but the BC delegation persisted and ultimately succeeded.

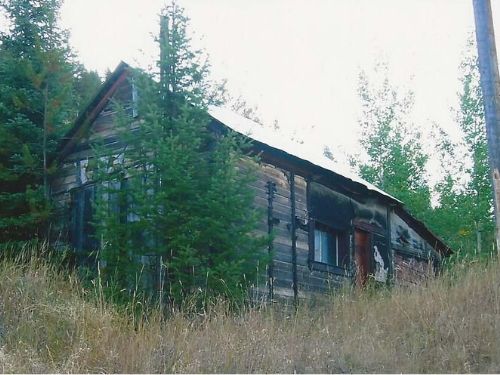

Photo of the shack that the Iwasaki family were given to live in after they were forced off their 598 acre farm. (Photo courtesy of Chuck Tasaka).

B.C. opposition leader Harold Winch and Hart together called MP Ian Mackenzie, a well-known racist, on Feb. 23, 1942, to demand that all Japanese Canadians be detained. This despite the fact that the army and RCMP declared that they did not believe that Japanese Canadians were a security risk. (Contrast this with the treatment of German and Italian Canadian communities who were not interned on masse nor dispossessed.)

The BC government appointed Winch, Pearson and Maitland to the advisory committee to the BC Security Commission that supervised the uprooting of Japanese Canadians and ordered the provincial police to round up the community and to patrol the incarceration camps throughout the province. The commission separated men from their wives, splitting up families at this difficult time, causing trauma that echoes across generations.

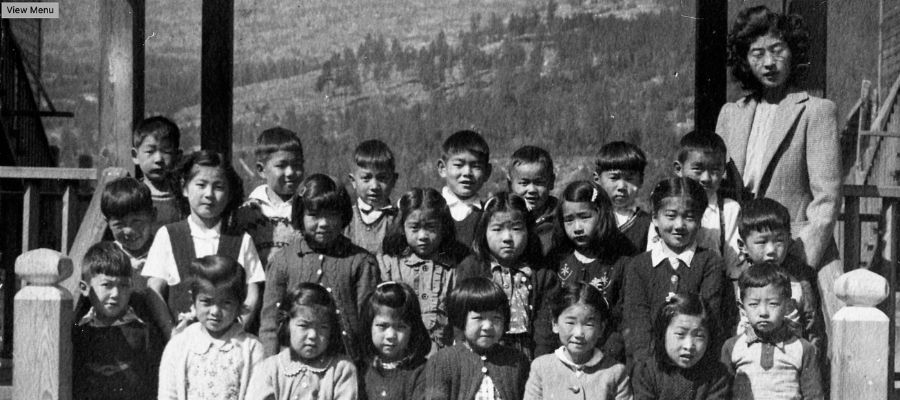

The BC government refused to pay for the education of Japanese Canadian children held in the camps, although it was a provincial responsibility.

The BC government enabled the mass dispossession of all property of Japanese Canadians without compensation. Contrast this to the US where little property was confiscated.

After the war, BC legislators demanded that Japanese Canadians be sent to Japan, a country most had never seen, or dispersed across the country. Today, 60 per cent of the community resides outside the province. Again, contrast this to the US, where there were few exiles or deportations.

BC premier Byron Johnson refused to allow Japanese Canadians to return to the coast until April 1949. Yet again contrast this to the US, where Japanese Americans were able to return to their homes before the end of the war.

We hope Horgan’s omission, which has deeply offended Japanese Canadians, does not indicate that he doesn’t take their concerns seriously.

Horgan and his government have an opportunity to acknowledge and set right this historical blight. We look forward to the government arriving at an agreement with the National Association of Japanese Canadians that appropriately addresses this historic wrong.

Demonstrations against racism are sweeping much of the world. The tide of history will be on the side of governments who act to rectify and address their racist past.

Swimming Upstream: The Japanese-Canadian struggle for justice in BC

The video below from the Canada Race Relations Foundation does a good job of summarizing the plight of the Japanese Canadians.

Topics: Racism & racial justice