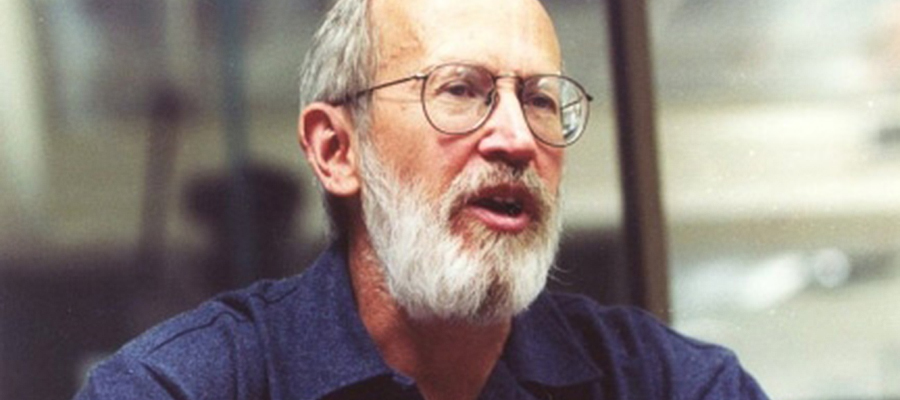

Remembering Murray Dobbin—activist, intellectual, mentor, friend

Neoliberal myth-buster. Far right exposer. Movement philosopher. Activist mentor. Murray Dobbin was all of these.

On Sept. 8, our good friend and comrade Murray died at age 76. Murray was not ready to leave, but after two-and-a-half years the inexorable brutality of cancer led him to choose medical assistance in dying to end his life on his own terms.

Murray’s fighting spirit, sharp intellect and unwavering values guided him through decades of work in service of a better world. We read him and heard him before we knew him. The man we read and listened to on the radio and giving speeches directed his righteous anger at the neoliberal project unfolding in the 1980s and ’90s. But the man we got to know was mostly of good humour—still with a strain of that suitable outrage, but kind and supportive.

Many familiar with Murray’s work have known him mainly as a writer. And for years he wrote a political commentary column that appeared in The Tyee and Rabble. He wrote numerous popular papers for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. And Murray was the author of five outstanding books, including cutting biographies of Preston Manning (he was tracking the rise of the far right in Canada long before others) and Paul Martin (whom he dubbed “the CEO of Canada”), and the 1998 book The Myth of the Good Corporate Citizen: Democracy Under the Rule of Big Business.

We read him and heard him before we knew him.

Less known were the countless hours and many years Murray spent donating his time on the national boards of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the Council of Canadians and Canadians for Tax Fairness. In 2001, Murray was a key architect (along with Judy Rebick, Jim Stanford, Svend Robinson and Libby Davies) of the New Politics Initiative, an endeavour to renew the NDP and strengthen its connections to social movements.

His longtime friends Davies and Kim Elliott, in a lovely tribute they wrote on Rabble recall, “He was a giant of the Canadian left, and had a profound influence on contemporary thinking and action.”

Maude Barlow, longtime chair of the Council of Canadians, said of Murray’s passing, “Murray was a fierce defender of social justice and spent every waking minute in its service. He made a huge contribution to many organizations and to our movement. He will be sorely missed.”

Seth recalls: in the days when Murray was still just an icon to me, his CBC Radio Ideas documentary on New Zealand’s neoliberal experiment stood out to me. And I will never forget attending a Fraser Institute student conference in the mid-1990s (I was there as an interloper doing MA thesis research), listening to a speaker laud the New Zealand model, and I couldn’t help myself—I had to go to the mic and offer some counter points, drawing upon Murray’s work. In response, Michael Walker, founder of the right-wing Fraser Institute, came storming up to the podium (pushing aside whoever was supposed to be there) to tell the audience that, while one should always do one’s research, whatever you do, “Don’t listen to Murray Dobbin!” Well, that seemed to me a very good reason to pay special attention to Murray.

Then, when we were hired in the early days of the BC office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, we had the pleasure of getting to know Murray and we quickly became friends as well as colleagues. Murray threw himself into the CCPA–BC office project and spent years as an active research associate and board member.

He was a giant of the Canadian left, and had a profound influence on contemporary thinking and action.

Shannon recalls: The friend and mentor we got to know was kind, supportive and wickedly funny—in addition to being a relentless fighter of neoliberalism and its promoters. True mentorship is bringing other people along by treating them as capable peers. As a young person just finding my way in social change movements, Murray treated me as an equal from day one. He helped me figure out what it meant to build intellectual infrastructure for progressives, and inspired self-confidence and clarity of purpose. I know he had this effect on others around us too. It’s a remarkable quality (not least for someone who suffered no fools!).

Murray, along with his life partner and political soulmate for 40 years, Ellen Gould, was someone who lived his values.

He hailed from Saskatchewan, where he began a journalism career with the CBC. He and Ellen met in Saskatchewan, where they were active in the peace movement and in fighting the privatizations of the Grant Devine government of the 1980s. They shared an interest in popular education and spent time at the Highlander Folk School in rural Tennessee learning from Myles Horton. Murray carried the organizing insights garnered there and elsewhere into his writing and the political counsel he offered, as one can hear listening to this 2014 Rabble and CCPA podcast on reinventing democracy (at which Murray shared the stage with Duncan Cameron, Anjali Appadurai, Iglika Ivanova and Damien Gillis).

The friend and mentor we got to know was kind, supportive and wickedly funny.

He turned down well-paying jobs so that he could focus on the work, research and writing for which he was passionate. He didn’t want to sign on to paid gigs that would compromise his independence and ability to speak his truth. Murray and Ellen lived modestly and in an environmentally conscious manner. He was a committed social justice activist; someone who not only wrote and spoke but showed up for protests and solidarity. He was ahead of the curve on many issues, such as his MA research and subsequent 1981 book on early Métis leaders Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris. When new youth initiatives (such as Check Your Head) or the New Politics Initiative were taking shape, Murray was there to encourage and support.

But Murray and Ellen also understood that doing good politics required a human and social element; we are, after all, social beings, and they made sure to create space and time in their home for progressives to forge community. “People need those social connections,” Murray would say. His favourite slogan, according to Ellen, was “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

“While Murray’s political persona was fierce,” says Ellen, “he was a total sweetheart to share a life with.” When Murray and Ellen moved away from Vancouver, the Lower Mainland progressive scene lost a local mentor, but Powell River gained a pair of activists who brought their considerable energy to local politics and community building.

Murray had a deep sense of connection to place, including the boreal forest of northern Saskatchewan where he and Ellen spent time every summer, until recently, in a cabin he built with an expert Métis cabin-builder. In Powell River, they spent countless hours hiking, swimming and paddling, even as Murray’s illness became critical. Murray loved to spend time outdoors with visiting friends, sharing his delight in his surroundings. Those visits were filled with talk of politics and current events—mixed with debates about the merits of camping (Murray in favour, Ellen having none of it), tips for the best places to eat out or get local farm produce, and stories of youthful misadventures.

Tyee founding editor David Beers says, “Murray was a courageous voice in service of social justice. And he was an incredible researcher in service of his arguments. He wrote with verve and conviction and people clearly connected. From the earliest days of The Tyee until 2016, he published 231 columns in our pages, which means I had the pleasure of editing him often. And sometimes the extra pleasure of sharing a cup of coffee in person. Those were lively conversations because Murray was always alive to the political moment. Not Ottawa soap operas. Those didn’t so much interest him. For him it was politics with a capital ‘P.’ He cared really deeply, wanted so much for Canada, never wavered from his principles of the highest order. He was inspirational in his fundamental belief that progressive political movements can make a better world.”

He turned down well-paying jobs so that he could focus on the work, research and writing for which he was passionate.

Naomi Klein, in a note to Murray just before he died, wrote, “Your energy, voice and vision are with us and will only continue to gain power and resonance. You saw so much of the hardship we are living through coming. You tried every creative tool to get in the way. And, as you did, you left a rich legacy: of organizing, writing, editing, relationship-building, and of careful strategic thinking that is finally being picked up and put into action by a new generation of leaders. Reading back over our correspondence spanning two decades, I am struck that you never lost your excitement or sense of possibility, no matter the setbacks or very real frustrations. The stakes were too damn high, and you were convinced that the left base was ours to build. I still believe that you were right. You always knew, long before I was ready to listen, that true power lay at the intersection of social movements, organized local communities (like yours) and state power. I hope, in the current wave of movement-rooted candidates, you see the fruits of your own patient intellectual labour. Murray, you were on the right side of every fight that mattered, and you waged those fights with fierce focus and great gentleness. A rare gentle-man you are, and I feel blessed to have been in conversation with you over these many years, and alongside you in many fights.”

Murray wrestled with how tough it could be to achieve social progress in the face of the neoliberal onslaught. Yet he remained engaged and never let that stop him from thinking and strategizing about how we could do better, always laser-focused on understanding how power operates and how it can be challenged. When you get discouraged yet fight on regardless because you feel an obligation to those yet to come, that is a special order of commitment. That was Murray.

Thank you Murray, for the comradeship, for the encouragement, for the wisdom and insight, for the friendship.

Murray is survived by his long-term partner Ellen Gould, his brother Gary, and his sister Diane.

Donations in Murray Dobbin’s memory may be made to Canadians for Tax Fairness, on whose board Murray served as founding president. The CTF plans to establish a youth internship in Murray’s name. Another essay about Murray by CTF executive director Toby Sanger can be found here.

Topics: Democracy