What happened to the National Housing Strategy?

Launched in 2017, the National Housing Strategy (NHS) was billed as a major re-engagement by the federal government on affordable housing after more than two decades on the sidelines. Starting with a headline commitment of $40 billion when first announced and supplemented in subsequent budgets, the NHS is now ostensibly valued at more than $75 billion over ten years.

This post takes stock of the NHS to date, in terms of the overall federal spending effort on housing and the amount and nature of housing supported by the NHS. The headline commitment of $75 billion, in particular, substantially exaggerates actual federal expenditures on affordable housing. Where the NHS has played a role is in continuing support for existing social housing and, more recently, injecting funds to address homelessness.

When it comes to new affordable housing, however, the bottom line is that the NHS has delivered relatively little of what Canadians might consider to be affordable housing or social housing, in particular dedicated non-market and co-op rental housing. Market housing in Canada constitutes about 95% of the housing stock, and the NHS does not make any serious inroads into challenging that situation. If anything, the NHS is supporting the ongoing financialization of Canada’s housing stock by emphasizing low-interest loans to private developers building market rental housing.

The big picture on federal expenditures

A 2021 review of the NHS by the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) showed $37 billion in actual and planned federal budgetary expenditures over 10 years starting in 2018/19, compared to $75 billion in headline commitments. And $12 billion of the actual/planned total represents pre-existing commitments made prior to the NHS. Thus, only one-third ($25 billion) of the claimed $75 billion headline number represents new federal spending. If anything, the NHS is supporting the ongoing financialization of Canada’s housing stock.

In addition, the NHS headline number counts the provincial/territorial share of programs that require cost-matching with the federal government. That is, it conflates federal expenditures with provincial expenditures, and assumes provincial governments will take up the cost matching.

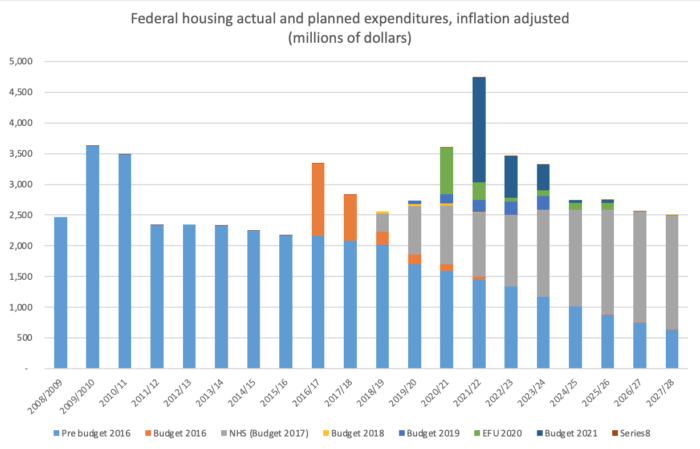

To get a better sense of federal effort we can look at planned and actual housing expenditures under the NHS and before. Figure 1 reproduces the PBO’s estimates in nominal terms then adjusts for inflation using the consumer price index.2 The addition of 2017 NHS planned spending (in grey) leads to a modest increase in federal expenditures relative to early 2010s levels. A notable bump in expenditures from the 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update (green) and the 2021 Budget (dark blue) primarily reflects the Rapid Housing Initiative (RHI), aimed at the acquisition of social and supportive housing, including the purchases of hotels for conversion.

Figure 1

Source: Data from CMHC as provided to Parliamentary Budget Office 2019 report on NHS, 2019 Budget, 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update, 2021 Budget.

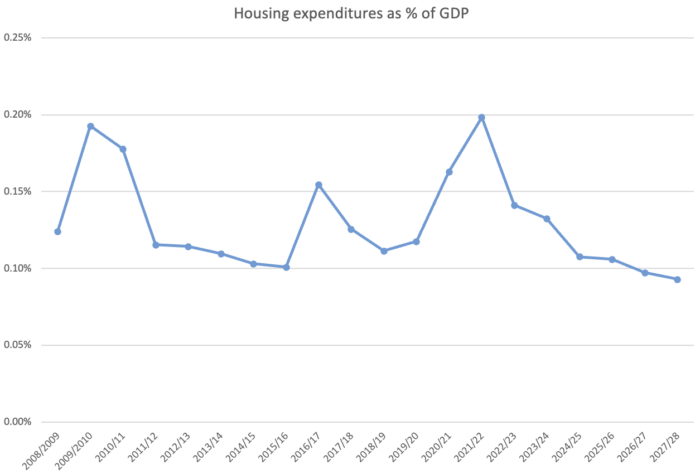

Figure 2 looks at the federal effort over time relative to the size of the economy. The overall federal effort is relatively small, ranging from 0.1 to 0.2% of GDP. Apart from a boost from the RHI in the 2021/22 fiscal year, projected expenditures are forecast to be similar to expenditures going back to 2008 and are declining as a share of GDP going forward.

Much larger infusions of funding will be needed in the 2022 and subsequent budgets if the federal government is to live up to the rhetoric of the NHS. The federal government certainly has the fiscal capacity to engage in broad-based development of non-market housing that would actually have a meaningful impact on housing affordability. The good news is that upfront capital costs of building housing would be repaid over time in rents. However, the commitment to a big bang rollout of dedicated non-market housing has been missing.

Figure 2

Source: Housing data from PBO and federal budgets as per Figure 1. GDP data from Statistics Canada up to 2000 and beyond from federal Economic and Fiscal Update 2021.

A closer look at NHS funding streams

As headline numbers can span up to a decade, we need to see what projects and number of units have been approved, what’s under development and construction, and, finally, what has been completed. Beyond the numbers of units, we are also interested in the mix of loans versus grants, whether funding is going to non-profits versus for-profit developers, and how much is new construction versus repairs or renovations of existing units. The commitment to a big bang rollout of dedicated non-market housing has been missing.

- Rental Construction Financing Initiative (RCFI), which supports new market rental housing (for-profit development). About 40% of the headline NHS number is for low-interest loans under the RCFI.

- National Housing Co-Investment Fund (NHCI), which funds social (co-op and non-market) housing in partnership with non-profits and other levels of government. Both grants and loans are available for new construction as well as repairs and retrofits of existing housing.

- Rapid Housing Initiative (RHI) is a newer initiative that supports the acquisition of social and supportive housing with a budget of $2.5 billion from the 2020 Fall Economic Statement and the 2021 Budget. The RHI was been used, for example, in Vancouver during COVID to buy hotels for conversion to housing for homeless people.

- Affordable Housing Innovation Fund is intended to develop affordable housing via “innovative business approaches and building techniques.” These appear to be mostly loans, but few details have been released.

- Federal Lands Initiative aims to “create 4,000 housing units by transferring surplus federal lands and buildings to housing providers at low or no cost.” While the idea of using existing federally-owned public land has merit, very little has come from this initiative.

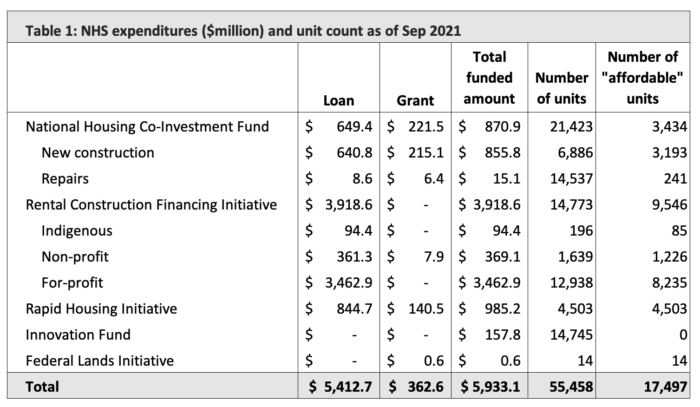

The NHS publishes a spreadsheet of announced projects. Between August 2017 and September 30, 2021, the NHS had announced projects totalling almost $6 billion, supporting over 55,000 new units. These are broken down in Table 1.

Table 1: NHS expenditures ($million) and unit count as of Sept 2021.

Notes: The quotes on “affordable” units reflects different definitions as discussed in the text. Source: Government of Canada, NHS Announced Projects, https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/place-to-call-home/nhs/nhs-announced-projects.xlsx, accessed February 3, 2022.

For the National Housing Co-Investment Fund (NHCF), most of the units funded are repairs and renewals as opposed to new construction, with the vast bulk of these from the Toronto Community Housing Corporation.

Three quarters (75%) of NHCF funding is in the form of loans not grants. All of the Rental Construction Financing Initiative (RCFI) is loans, and 88% of RCFI loans (and 75% of projects) went to for-profit developers, compared to 9.2% to non-profits and 2.4% to Indigenous projects.

Only $363 million from the NHS represented new federal investment (grants and contributions) in the construction of new dedicated affordable housing, up to Sept 2021. And 39% of this is the Rapid Housing Initiative (RHI), which was only announced in Fall 2020 and was not part of the original NHS. This is a far cry from the rhetoric of the NHS and the $75 billion headline number.

The RCFI has also been criticized for making it hard for non-profit developers to access loans due to requirements for upfront capital. For-profit developers, perversely, have been better able to access loans for projects that end up building more expensive rental housing. Additional NHS data released upon request to NDP housing critic Jenny Kwan show that the RCFI for-profit projects yielded much higher average rents.

The same data also show that as of August 2020 average processing times were just over a year for the RCFI and 1.5 years for NHCF before getting a project approved. Of course, it will take even more time for permitting and construction before anyone can move in. The RCFI for-profit projects yielded much higher average rents.

Is the NHS delivering on affordability?

The term affordability is used frequently but has different meanings so it’s worth considering how much of newly constructed housing will be genuinely affordable. By its own accounting, as seen in Table 1, some 32% of units are counted as affordable (including repairs and new construction). However, even this may overstate the amount of affordable housing due to different definitions.

The PBO notes that “The National Housing Co-Investment Fund only requires that 30% of units be offered at 80% of median market rent. And, its prioritization and incentivization scoring provides no reward for offering more than 51% of units at 80% of median market rent.”

The RCFI has different affordability criteria, requiring that 20% of units meet a benchmark of rent at less than 30% of median family income (as determined for each city), as opposed to median market rent. The PBO states “30% of median total income for all families in the area is generally higher than the rent for new private market rental developments.”3 In Vancouver, this calculation would mean that 20% of the units would be available at $2,063 per month, while the remaining units would rent for more. The RCFI is arguably clearly a program for the middle class rather than those most in need of affordable housing.

Other NHS housing supports

In addition to new construction, there are other key initiatives in the NHS that represent ongoing funding supports. These are important but do not get the attention that is reserved for new housing projects.

- Community Housing Initiative, which provides ongoing subsidies (about $1 billion per year) to maintain affordability in older social housing projects that were reaching the end of their operating agreements with CMHC.

- Reaching Home, about $215 million per year towards homelessness, provided through Employment and Social Development Canada, not CMHC.

- Canada Housing Benefit, $2 billion federal money over eight years, cost-shared with the provinces/territories, to provide funding directly to families and individuals in housing need. Three provinces (Alberta, Quebec and New Brunswick) have not signed agreements with the federal government for the CHB.

- First-time home buyer programs include a Shared Equity Mortgage Provider Fund and the First Time Home Buyer Incentive. The total budget associated with these programs is relatively small, but to the extent they are successful they add fuel to an already overheated housing market. They represent affordability only in a very narrow sense. New programs proposed in the Liberals’ election platform are reviewed here.

Not counted in these amounts but worth mentioning is a tax expenditure that benefits homeowners, the non-taxation of capital gains associated with principal residences. The Department of Finance estimates the foregone revenue associated with this tax treatment to be worth $7.8 billion in 2022, about double the annual expenditures on housing in recent years discussed above.

Outside of principal residences, all other capital gains associated with real estate also benefit from having only half of any realized gains counted as income for tax purposes. Together these are tantamount to subsidies to real estate investment and form part of the explanation for skyrocketing housing prices in recent years.

Making housing a human right

The NHS has been more successful at delivering big headline numbers than in producing actual housing. While the NHS rhetorically speaks to making housing a human right, there has yet to be a meaningful fiscal commitment to make it so. At best, we can say that the NHS maintains previous federal effort on housing supports, has spurred some new market rental housing, and is slowly rolling out a modest amount of new social housing. While the NHS rhetorically speaks to making housing a human right, there has yet to be a meaningful fiscal commitment to make it so.

While the ramp up period for the NHS has been very slow, now is the time for funds to flow so that real projects can get off the ground. Significantly more fiscal effort–grants aimed at reducing financialization and reliance on markets for housing–will be needed in subsequent budgets for the NHS to live up to its promise of making housing a human right.

This research is supported by a grant from the Vancouver Foundation. The author would like to thank Shannon Daub, Nick Falvo, Alex Hemingway, David Hulchanski, Steve Pomeroy and Greg Suttor for their comments on an earlier version of this post.

Notes

1. The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) 2019 report comments, “Contributions and loans are fundamentally different in their cost to government and ability to influence behaviour. Because loans must be repaid, they provide less of a financial incentive than a direct contribution of the same face value. The budgetary costs associated with loan programs arises from provisions for credit risks or insurance, interest timing mismatch and operating costs. For example, the budgetary cost of the $3.75 billion in loans available under the Rental Construction Financing Initiative (prior to Budget 2019) is only $0.3 billion.”

2. Original tables from CMHC provided to the PBO, received via David Hulchanski access to information request. The PBO published report strangely did not adjust for inflation so this has been corrected.

3. PBO 2019 report, footnote 33.

Topics: Housing & homelessness