New survey data shines light on the extent and impacts of precarious employment in BC

The rise of the “gig economy” and on-demand work through online platforms like Uber and Skip the Dishes has ignited public debate about precarious work and what makes a “good job.”

We all know that precarious work existed long before Uber and is not limited to the gig economy. But government efforts to develop an effective precarious work strategy for BC—as promised in the 2020 election—are hampered by the lack of data on the scale and impacts of precarious work. Statistics Canada simply does not collect the regular, timely data on many important dimensions of precarious employment that are needed to understand the security and quality of jobs in today’s labour market or track any changes over time.

So we embarked on our own data collection project to gather new evidence on the scale and unequal impacts of precarious work in our province. Our pilot BC Precarity Survey was completed by over 3,000 workers aged 25 to 65 from across BC in the late fall of 2019. It provides a unique snapshot of the provincial labour market at a time of historically low unemployment and relative labour market strength just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

You can read more about the findings from the pilot BC Precarity Survey in our new report, But is it a good job?. The upshot? We found that precarious work is a widespread problem in BC, contributing to socio-economic and racial inequalities and putting strain on families and communities across the province.

What is precarious work?

Precarious work can mean not having dependable hours, no job security, few (if any) benefits, or a lack of meaningful access to workplace rights and protections—the kind of work arrangements that create insecurity and hardship for people and their families. Exactly what makes a job precarious is shaped by the ever-changing realities of local job markets and therefore looks different in different places and time periods. This makes defining precarious work a challenge, and yet defining it is vital for understanding and addressing it.

In this study, we measured precarious employment in two different ways:

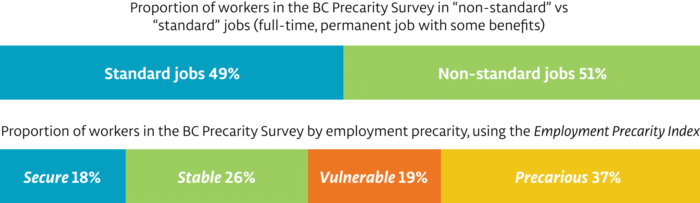

First, we looked at whether survey respondents had “standard” jobs (i.e., a full-time, permanent job with a single employer that includes at least some benefits). However, we found that some workers with standard jobs still experienced aspects of precarity, such as unpredictable scheduling, working multiple jobs at the same time or lacking access to important workplace benefits like extended health coverage.

Second, we used the Employment Precarity Index developed by an earlier research initiative called the Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario (PEPSO) project. The Index allows us to combine a broader range of dimensions of precarity into a single measure and categorize workers’ employment experiences into one of four employment security categories: Secure, Stable, Vulnerable and Precarious.

The “standard job” was not all that common and was unequally available

The BC Precarity survey found that the standard job was not all that common: only 49% of BC workers we surveyed had standard jobs. This is concerning because our system of workplace rights and protections—including access to workers’ compensation, employment insurance and parental leave, pensions, extended health coverage, paid sick time, etc.—is still largely designed around this model of the standard job.

We found that women (especially racialized and Indigenous women), younger workers aged 25 to 34, Indigenous workers and recent immigrants were less likely to have a standard job. Standard jobs were more common in Metro Vancouver than elsewhere in the province and least common in the BC Interior.

Some workers in standard jobs experienced some elements of precarity

A significant minority of people in standard jobs reported frequent, unexpected scheduling changes (21%) and/or working multiple jobs at the same time (18%). Many workers in standard jobs did not have access to important workplace benefits, such as extended health coverage (15%) or retirement benefits (30%). Less than half (43%) received employer-provided training within the last year.

In other words, having a standard job was not a guarantee of job quality and security. This is why we turned to the Employment Precarity Index to capture a broader range of dimensions of precarious work. Here’s what we found.

The Employment Precarity Index shows a polarized BC job market pre-pandemic

We found that 37% of survey respondents had Precarious jobs and only 18% were in Secure jobs. Such high levels of precarity amid the strong pre-pandemic labour market suggest that the problems are likely worse today. Since 2019, rising inflation has eaten into wages, a problem that is made worse when workers and their families face unpredictable, insecure employment and/or do not have access to employer-provided benefits.

Secure jobs were unequally available to different groups of British Columbians

Racialized and Indigenous workers were significantly less likely than white workers to have Secure jobs. Secure jobs were slightly less common in Northern BC and the Interior than in Metro Vancouver and Vancouver Island.

More than half of recent immigrants (less than 10 years in Canada) were in Precarious jobs (55%), the highest proportion of any group in our survey. Younger workers (aged 25 to 34) were more likely to be in Precarious jobs.

Precarious work was strongly associated with low incomes, but not all Precarious jobs were low-paid

Nearly two-thirds of workers earning less than $40,000 per year had Precarious jobs—64%, compared with only 23% of those earning above $80,000. However, not all Precarious jobs were associated with low employment incomes—about a third (34%) had middle incomes and 18% had higher incomes.

Employment precarity had negative effects on individuals, families and communities

Workers in Precarious jobs—especially those with low incomes—were more likely to report poorer physical and mental health.

Among caregivers of children, those in Precarious employment were far less likely to be able to afford school supplies and trips. They were also much less likely to have time to attend or volunteer at school and community-related events and activities. This reveals that employment precarity impacts children’s experiences and opportunities.

We found that caregivers of children in Precarious jobs were four times more likely to report that lack of access to child care impacted their ability to work compared with those in Secure jobs. Recent immigrant parents were particularly impacted by caregiving responsibilities—60% reported that lack of access to child care negatively affected their own and/or their spouse’s ability to work (compared to 37% of non-immigrants). They were also much more likely to report that caring for an adult (e.g., an elder) negatively affected their or their spouse’s ability to work.

Many survey respondents said work demands and job strain interfered with their family responsibilities on a weekly or daily basis, affecting not only them but also their families.

The solutions? Better data collection and immediate government action

This first-of-its-kind study on multiple dimensions of employment precarity in BC highlights the need for more data collection in BC but also nationally. The pandemic—which started just after the BC Precarity Survey was conducted—has exposed just how little we know about job quality and job security in Canada. It also pushed Statistics Canada to start capturing data on racialized identity and access to benefits in the monthly Labour Force Survey (though the benefits data have not been publicly released at the time of writing). Statistics Canada also ran a one-off Survey on Quality of Employment in early 2020 but the results weren’t released until May 2022. These are welcome initiatives, but we need regular, timely data at the regional and local levels on multiple dimensions of precarity to fully understand its unequal impacts in BC and beyond.

At the same time, our findings suggest that we must act now to tackle the significant and uneven burden of precarious work. Our analysis confirms that the burden of precarity falls more heavily on racialized and immigrant communities, Indigenous peoples, women and lower-income groups. In other words, precarious employment compounds systemic, intersecting inequalities in our province.

The good news is that the BC government has the power to improve the lives of workers and families by strengthening workplace rights and protections, enforcing them proactively and regularly reviewing legislation to keep up with rapidly changing labour markets. Strengthening worker voices, such as by making it easier to unionize and using sectoral bargaining models, can improve working conditions and reduce gender/racial pay inequities. Expanding access and portability of benefits, addressing unpaid care work and access to child care and bringing in strong pay equity legislation are additional ways to reduce precarity in BC while supporting family and community wellbeing. The recent introduction of five days of paid sick leave in BC and federal efforts to extend dental coverage and reduce child care fees will help many precarious workers, but more action is needed.

The pilot BC Precarity Survey is part of The Understanding Precarity in BC project that will generate needed data on the extent and nature of precarious employment in BC.

Topics: Economy, Employment & labour, First Nations & Indigenous, Immigrants & refugees, Poverty, inequality & welfare, UP–BC, Women