Public libraries are becoming the new social safety net

Public libraries in British Columbia are evolving beyond spaces of quiet contemplation, equipped with card catalogues and encyclopaedias. In a time of increased Internet use and communication via social media, the way we access knowledge and use the library is changing. We are seeing digital storytelling and inspiration labs, access to design software, e-readers and digital book lending, yoga classes, and purpose-designed ‘living room’ areas in our libraries. For the most part, these changes are welcomed.

But other changes are taking place that, unfortunately, are more difficult to resolve. Increasingly, the types of knowledge people seek are changing. Questions about housing, immigrant support services, governmental forms, and job skills are increasingly answered using information provided at the library. But should they be?

Libraries across the province are filling the gaps left by decades of cuts to funding for important programs and services. In many ways, public libraries are providing a social safety net for the most marginalized people in our province—working on the front lines in the fight against poverty, and grappling with difficult questions regarding homelessness, poverty and public space. Yet, this is not technically their mandate. Nor is the governmental and financial support they receive sufficient to adequately respond to rapid changes in the types of knowledge patrons require.

Public libraries are providing a social safety net for the most marginalized people in our province and working on the front lines in the fight against poverty.

I spoke with dozens of library staff and board trustees across the Lower Mainland as part of SSHRC-funded research I conducted in 2014-15, and listened to numerous stories about the needs of homeless patrons in the library and how librarians attempt to make the library an inclusive space for all.

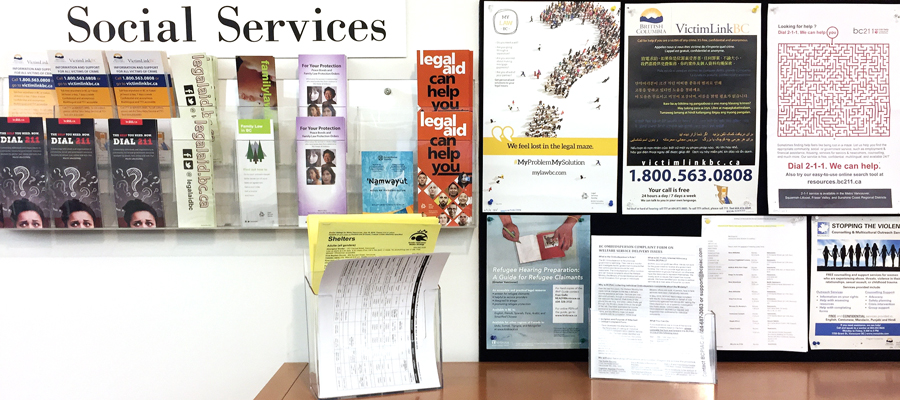

Library staff members regularly navigate complaints from housed patrons while trying to support their homeless patrons to find safe shelter during the day, sleep in safety, and enjoy the space of the library. One librarian proudly told me that she routinely offers a regular homeless patron a cup of tea to help him stay awake and warm in the library. Another librarian in Surrey discussed how she supports patrons who are fleeing domestic violence, and accessing shelters, detox centres, and local food banks. Due to the demand for this type of knowledge, one Surrey librarian created a pamphlet listing key social services in the municipality; in time, a poverty reduction program offered by the City adopted this pamphlet.

All libraries in the Lower Mainland are facing similar challenges. Vancouver has long had a special library card for people without an address. Librarians across the region are supporting patrons in filling out governmental forms such as welfare applications, finding housing, accessing a range of support services, and, recently, they are seeing increased overdoses in the library. As government services move increasingly to online spaces, those without personal Internet access are turning more and more to public access Internet terminals at libraries. Many of our public libraries have discussed or proposed hiring an in-house social worker—to mixed responses by library boards and municipal governments. Unfortunately, situations like these are not unique to the Lower Mainland and are increasingly visible across the province.

Clearly, librarians are doing much more than providing “access to knowledge,” as described in the (former) BC Liberal government’s 2016 report on libraries.1

If librarians are supporting individuals impacted by governmental budget cuts and years of underfunding, who is supporting our librarians?

Though libraries in British Columbia have significant public and governmental support, this question is still a difficult one.

The way we understand the role of libraries in our cities, regions and province affects how they are governed and funded.

Public libraries are caught in a messy web of governance. They are technically autonomous institutions but are legislated by the provincial government, governed by a Public Library Board (of locally appointed trustees), and primarily funded by municipal and regional governments (with minimal grants from the province). At the provincial level, libraries are governed under the Ministry of Education. However, the former BC Liberal government’s 2016 Strategic Plan for libraries is completely inadequate for addressing the real types of knowledge libraries are providing. Further, major decisions regarding library budgets rest with municipal and regional governments. Once again, as with the regulation of housing, municipal governments are left to make important decisions beyond the scope of their jurisdiction.

Clearly, the way we understand the role of libraries in our cities, regions and province affects how they are governed and funded.

As the types of knowledge people are accessing change, the ways in which libraries are governed should also change. Libraries are holding one of the strings of an ever-changing social safety net in our province. Instead of being under the purview of the Ministry of Education, perhaps libraries should be governed under the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction. Librarians should be invited to the table to develop the Poverty Reduction Strategy and a Homelessness Action Plan.

As the new provincial government repairs the social safety net left tattered by years of neglect, they must look at exactly what kind of knowledge libraries are now providing, and address the underlying reasons for this shift.

Notes

- British Columbia. Ministry of Education. Inspiring Libraries, Connecting Communities: a vision for public library service in British Columbia. 2016 (25 pgs.)

Topics: Poverty, inequality & welfare, Provincial budget & finance