Economic insecurity touches seniors’ lives in profound ways

In the spring of 2016, the CCPA’s Terra Poirier and photographer Caelie Frampton met with three local seniors to document their lived experience of poverty and inequality. The images and stories of these women paint a sobering picture of what life is like when the hardships of living with a low income are combined with the many overlapping challenges of aging—chronic disease, reduced mobility, declining health and the loss of spousal and community support.

Jagjit

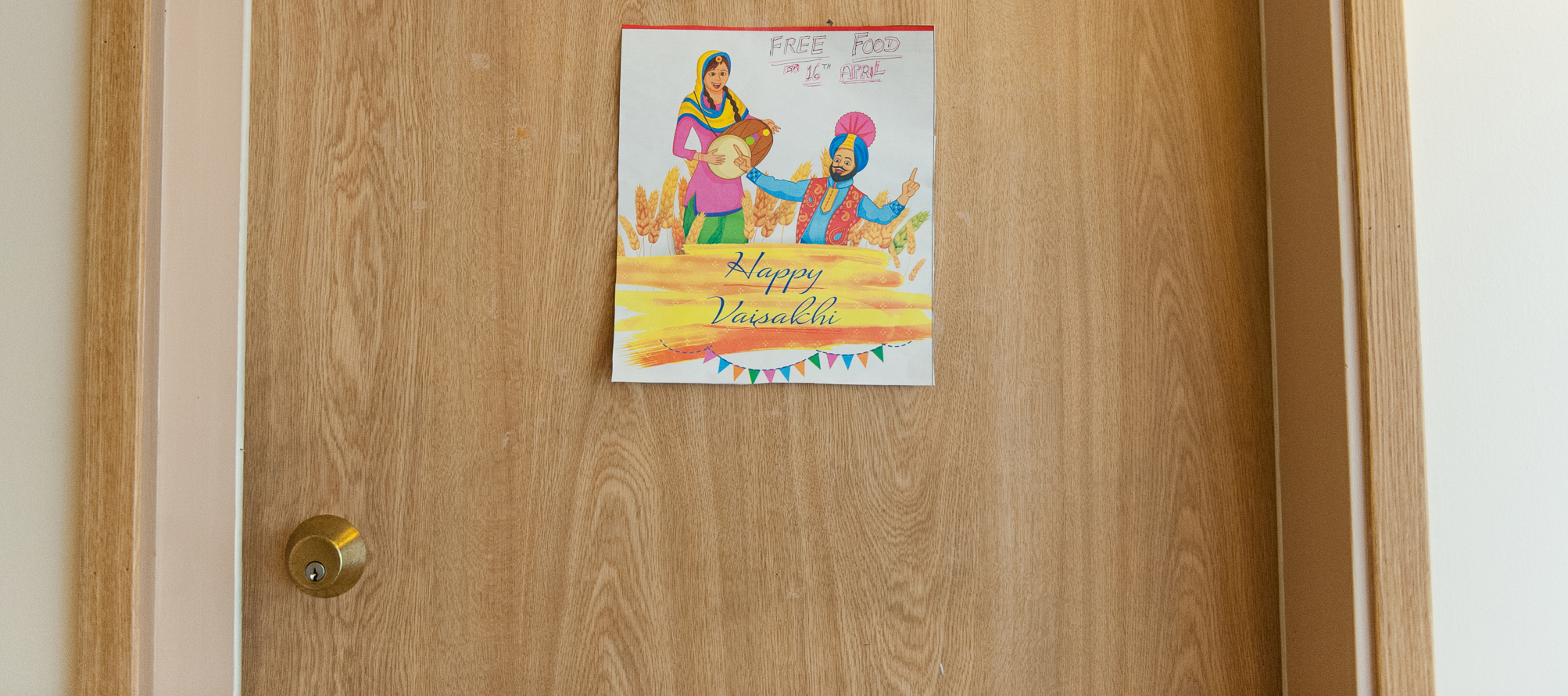

Jagjit, 75 at the time of the interview, has been living in Canada since 1991. Originally from India, Jagjit speaks six languages and spent many years working as an interpreter for a variety of health services in Metro Vancouver. She is an active community volunteer, participating in a number of seniors groups and events. At the time of interview, Jagjit was living with her husband, 88, in a publicly subsidized independent living facility. They have two children, neither of whom is able to provide day-to-day care for their parents (one lives out of town and the other has his own health challenges to manage).

Jagjit has diabetes and other health conditions and her husband’s poor health requires a great deal of care. Jagjit reported that she and her husband were only receiving one hour of home support a week, which was not enough to meet their needs. Jagjit said she was told that she is expected to be the primary caregiver for her husband.

They want to use me as his home support whereas I also need home support…. From morning to night, I am…cooking…sometimes breakfast, sometimes lunch, sometimes dinner, going to Superstore, buying groceries, going to pick up the medicines, doing the laundry, cleaning the house. —Jagjit

Many of the health care services Jagjit and her husband need are not covered by our public Medicare system, including dentures, vision care (Jagjit’s eyesight is deteriorating because of her diabetes) and home support. BC’s PharmaCare program requires considerable deductibles and co-payments for prescription drugs even for lower-income seniors.

Jagjit reported that she and her husband are paying 70% of their limited family income for their housing, which includes some services but does not include utilities or all meals. This is the standard charge for publicly subsidized independent living facilities. Jagjit finds it very difficult to make ends meet on their pensions.

Seniors are working…after retirement. Why are they working? Because [they don’t have] enough money. We have to buy groceries, cable, hydro, wi-fi, rent, the phone, and so many other things, medicines. The pension should be more. —Jagjit

Anita

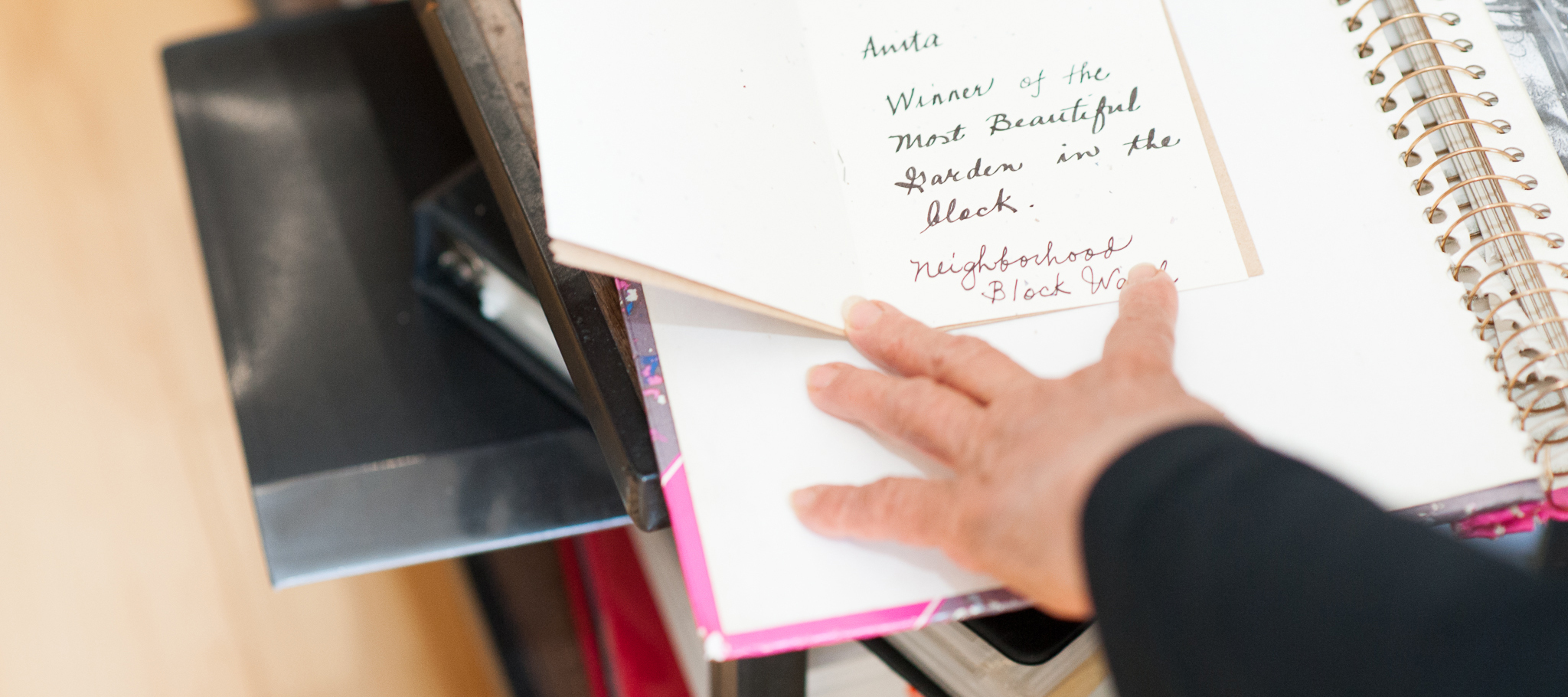

Anita, 78, is a poet, performer and gardener who is active with a number of community and cultural groups. In the Philippines she taught literature and social sciences at a state college but had to leave her career behind in 1994—in order to come to Canada to care for her elderly mother and her sister, who needed help recovering from surgery. “They didn’t have anybody, so I had to resign from my job.” After her sister recovered, Anita worked as a caregiver and then later at other service jobs.

They didn’t have anybody, so I had to resign from my job. —Anita

As Anita’s experience shows, lack of access to publicly funded home support and rehabilitation services puts enormous pressure on the shoulders of women to become the caregivers for elderly, ill or disabled family members. Sometimes this causes families to undergo massive upheaval, and forces caregivers to leave their careers and face an increased risk of poverty in old age as they are unable to save for retirement.

For years, Anita lived in a house that her sister owned, but once her sister was no longer able to use the stairs they had to move to a rental apartment. After her sister’s death in 2015, Anita was evicted.

Anita has a low income and is not easily able to climb stairs, so she needed an affordable and physically accessible apartment. “I am afraid I might fall and hurt myself,” she told us.

I was really worried when I was looking for a place. —Anita

She applied for social housing but the wait lists were long both for BC Housing and for other subsidized housing options run by non-profits. Anita couldn’t wait for social housing and searched in the private rental market where rents were high and age discrimination was surprisingly common. Anita shared that upon learning her age or that she was retired, landlords and managers would stop responding to her calls or would reject her application outright.

Anita was lucky to find a ground floor bachelor apartment and feels that she was only able to do so by knowing someone who lived in the building. She is close to public transit, but misses her old neighbourhood where she was able to more easily access grocery stores and other services.

When people ask her why she does so many activities, Anita replies: “If I don’t move, I get sick. I want to share whatever I have…even my ideas I want to share. That’s why I write poetry.”

Rama

Rama, 76, grew up in the Punjab in India, and moved to Canada in 1970. Before retirement, she worked in the kitchen of a seniors facility, and then as a janitor downtown and at a local university. At the time of our interview, Rama lived alone in her house of 44 years, which she used to share with her late husband. She owns her own home, which keeps housing costs low, but it is in need of major repairs that she cannot afford.

Rama has three daughters—one in Vancouver and two in Surrey. Since she had open-heart surgery in 2013, her ability to travel distances has been severely curtailed; she now needs to use a walker and travel by HandyDart, making her dependent on her family to come to her. Before her surgery, Rama enjoyed visiting her children and grandchildren and going out to access community services and attend events, but she reported that she is not able to do that as frequently now. Rama also loves to cook, and told us how much she enjoyed cooking for large groups of friends and family when she was in better health.

Rama told us that after her surgery she received home support for two months but the scope of the services provided was very limited, only covering her most basic needs—meals, baths and dishwashing. No other cleaning was covered and even now she finds it physically difficult to do most housework. Her daughter told us that they were not even informed that home support was available upon discharge from the hospital, and the bulk of her mother’s care fell to her until they learned (by word-of-mouth) that she might be eligible for home support. After the two months of home support were up, Rama said that it was not extended because the expectation was that her children would look after her, but they have their own families and jobs and most do not live nearby.

Rama shared that since 2002 she has been in a cycle of poor health with a number of medical conditions that require regular treatment and medication and that limit her ability to do certain activities. She told us that her prescription medication costs $600–700 per month, which she pays out of pocket. This is because PharmaCare will not cover her brand-name medication, even though she is not able to take the generic brand that is covered. Her medication eats up almost half of her $1,500 monthly income. Rama finds it very difficult to access other health care services when so much of the burden of their costs have been shifted to seniors.

Before we had 30 visits to the chiropractor, physio and massage. Then they cut it to 20, then we had 10, and now we have none. So if we want to go, it’s very difficult for us, every time, $50 per visit. —Rama

Since our visit in 2016, Rama’s health has taken a serious turn for the worse. One of her daughters is her primary caregiver and has had to relocate from her own home in Surrey in order to live with her mother full-time, another example of how a lack of support services causes upheaval for families.

* * *

Unfortunately, the struggles of Jagjit, Rama and Anita to find affordable housing, access home support when they need it and pay for their prescription medications are far too common in BC, as a new CCPA study released today shows.

The study, Poverty and Inequality Among British Columbia’s Seniors finds that while most seniors are doing okay—and a small group can be described as “well off”—a disturbingly large number struggle to meet their basic needs. Single women are at the highest risk of poverty.

We know from other research that Indigenous, immigrant and racialized seniors, seniors with chronic health problems and disabilities, those with lower levels of education and intermittent work histories, and gay, lesbian and transgender seniors are more likely to face economic insecurity. This is why policies designed to improve the lives of vulnerable seniors must embrace an intersectional approach and come hand-in-hand with poverty reduction, reforms to curb income and wealth inequality, and the gender gap in all generations. That’s the only way to help today’s struggling working-age adults avoid becoming tomorrow’s struggling seniors.

* * *

We are grateful to each participant for generously sharing their story with us. All information was current as of the time of the interviews.

For more information on how BC’s home and community care system for seniors is in crisis, read Privatization & Declining Access to BC Seniors’ Care: An urgent call for policy change, by Andy Longhurst, available on the CCPA website.

Topics: Features, Health care, Housing & homelessness, Poverty, inequality & welfare, Seniors, Women