The roots of our housing crisis: Austerity, debt and extreme speculation

We’re now 10 years on from the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression. Or, as our national mythology puts it, 10 years since Canada breathed a deep sigh of relief as the crisis mostly grazed our economy and financial system.

Since 2008, we’ve had 10 years of congratulatory back-patting over our system of financial regulation, 10 years of low inflation and low interest rates, 10 years of periodically oil-driven economic growth—and 10 years of exploding housing prices, of renovictions and demovictions, of working people pushed out of some cities and a real estate investment bonanza for the homegrown and foreign rich.

Ten years after the crisis, many Canadian cities are still in crisis. What follows is a look at the contours and roots of our urban housing crisis, and some avenues for exiting it in a way that would benefit the majority of people.

Housing boil and housing bubble

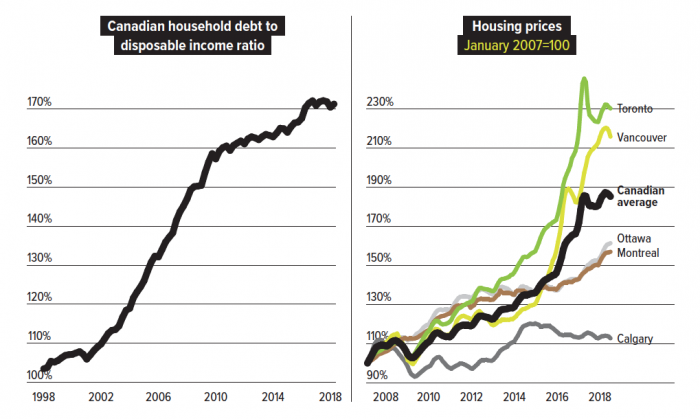

Average housing prices have grown by 80% Canada-wide since their lows in the winter of 2009, and more than doubled in Vancouver and Toronto (as measured by the widely used composite index maintained by the Canadian Real Estate Association, which incorporates everything from condos to single-family homes). Among Northern countries, only Hong Kong, Iceland and New Zealand saw bigger housing spikes over the same post-crisis period, according to the Bank of International Settlements.

In Canada, housing prices have been driven higher largely by land appreciation; it is not uncommon in major cities for the structures built on land to comprise just a small sliver of the value of a property. For example, between 2007 and 2018, real estate in British Columbia doubled in value, appreciating by nearly $1 trillion in inflation-adjusted terms, the vast majority of that a result of higher land values.

Meanwhile, as real estate prices have exploded, wage growth has been tepid at best. Between 2008 and 2017, the nominal median wage has gone up 22% Canada-wide and 20% in both Ontario and BC. Adjusted for inflation this is considerably less than one percentage point per year in real growth.

As real estate prices have exploded, wage growth has been tepid at best.

As housing prices have grown, the rate of home ownership, or the share of households that own the home in which they live (67.8% in 2016), remains near where it was before the crisis (68.4% in 2006). However, this drop is more pronounced when we consider that the home ownership rate had been climbing steadily from around 60% in 1971 to 69% in 2011.

These small changes in the overall rate also hide significantly greater inequality in home ownership. Whereas in 1971, those in the top 20% by income had a home ownership rate approximately 10% higher than those in the bottom fifth, this difference has grown severalfold in the ensuing decades. Millennials are entering home ownership in small numbers and later than their forebears: 50% of millennials own a home today compared with 55% of people their age in 1981.

The indebtedness of Canadian households has risen steadily since the crisis: from 150% of disposable income in 2008 to 170% today (though this pales in comparison with the twofold larger relative increase from 105% in 1998 to 150% a decade later). This 10-year increase diverges sharply from the situation in the United States, where households noticeably deleveraged after the crisis.

On the flipside, housing wealth is now staggeringly above 430% of disposable income (in January 2018) reflecting consistent increases since the 1990s. This is the paradox of the housing crisis: it has literally created wealth under the feet of one set of Canadians and foreign property owners—many of them already wealthy—while making simple existence for another set, in particular the urban poor, increasingly difficult.

Housing appreciation has turned some working people into millionaires, even if for now only on paper, and some regular people into rentiers. Real estate boosters love these examples of “rags to riches” and argue that there are other countries, notably Australia and several in Scandinavia, where household debt comprises an even higher percentage of household income than it does in Canada. The point, however, is not to argue about abstract statistics, but to see how runaway housing markets affect people.

Housing wealth is very unequally distributed. According to 2016 data from Statistics Canada, the top 20% of Canadian households own 63% of Canadian total net worth (assets minus mortgage debt) in real estate, while the bottom 40% own just 2% of the same. Properties that are not principal residences are more unequally distributed; the top quintile owns 81% of the net worth here.

In addition, while property prices and debt have accelerated, so have increases in rent for tenants in many cities, especially burdening those in the working class who did not buy into the property lottery at the “right” time.

It was not an accident

Far more interesting than how far Canadian housing is into bubble territory is the question of what impact the current run-up in values is having on Canadians, particularly the working class of the country. Here we need to go back further than just the past 10 years.

The start of the current expansion in Canadian mortgage debt and house prices coincided with the beginning of the era of stable low inflation and relatively low interest rates in the late 1990s, far preceding the 2008 financial crisis. This story about cheap credit and high expectations is one Stephen Poloz, the current governor of the Bank of Canada, likes to tell and there is some truth to it: financing real estate was relatively cheap already in the late 1990s.

But this early acceleration in Canada’s housing market coincided with another major shift, one that went far beyond a change in the price of loans.

In 1993, the last federal budget tabled by Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government ended all new federal funding for social housing construction outside of First Nations reserves. The feds were out of the business of creating new social housing, as they put it. This was a marked change from previous decades when the federal government helped finance about 20,000 units of social housing per year—from direct public housing in the 1960s and into the ‘70s to non-profit and co-op housing in the 1980s. In most provinces outside BC and Quebec, provincial governments did not pick up the slack following the 1993 announcement.

With the sudden imposition of social housing austerity, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) shifted from homebuilder to mortgage insurer. The move away from direct and indirect public provision only further solidified long-standing economic and cultural pressures toward home ownership. And with this move the federal government only accelerated the transformation of housing from human necessity into investment good, to be supplied almost exclusively by the private sector.

The federal government accelerated the transformation of housing from human necessity into investment good, to be supplied almost exclusively by the private sector.

Although Canada was ruled by market-friendly conservatives under Brian Mulroney in the 1980s, it was the Liberals, elected in 1993 under Chrétien, who made the greatest strides in transforming the Canadian state—shifting it towards neoliberalism and near-permanent austerity. Fiscal policy was defanged, now used to drastically reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, while monetary policy assumed the role of stimulating the economy, albeit within a strict inflation-targeting mandate.

With interest rates down from their 1980s highs, the state out of the housing game and new policies from the CMHC—including increased mortgage protection and significantly lower down-payment requirements (from 20% down to 5%)—the stage was set for the start of a long housing boom.

The early boom years were characterized by relative affordability. This was the time when the financialization of housing—its transformation into a major investment asset—was just taking off. Interest rates fell and house prices began to slowly recover from their 1990s recession lows. The bias toward home ownership, driven by fiscal contraction and monetary expansion, went hand-in-glove with long-standing policies at the provincial and city level such as exclusionary zoning and weak rent controls, as well as cultural beliefs about the primacy of the car or the importance of owning a single-family home.

The product of all these developments was a complex set of economic, legal and social factors that ultimately set the stage for the current affordability and liveability emergency in our cities. It is within these structures that power imbalances have evolved over the past decade.

In the immediate aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, triggered that September by the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, the Bank of Canada participated in the co-ordinated effort by many central banks to stabilize the global financial system. And while Stephen Harper ironically led one of the developed world’s more aggressive bouts of fiscal stimulus (which included substantial social housing investment) the trend toward slow-motion, structural austerity returned by the start of the 2010s.

While Vancouver and Toronto, as global cities, were the first to catch the bug of extreme housing speculation, the malady is now spreading to smaller cities and towns.

The Bank of Canada, on the other hand, continued to maintain very low interest rates, propping up the Canadian economy and doing its part to fight off a deeper global depression. With fiscal policy levers largely atrophied, monetary policy has taken up the long-term task of stimulating and stabilizing the economy—in Canada and much of the rest of the world.

Unfortunately, post-crisis monetary policy also stoked the flames of the already ongoing real estate boom. Lower short-term interest rates in a world of increasing inequality in income and wealth created fertile conditions for asset price inflation—a frenzied “search for yield” with everything from equities to collector art to real estate seeing enormous price gains globally.

Capital, in significant part domestic but also international, alighted on Canadian real estate as a safe, relatively high-return asset. Developers were only too happy to keep building safety deposit boxes in the sky, helping domestic and foreign capital—rather than people—find a home.

There is a tension here, however. Cheap credit is generally to be welcomed: it shifts the balance of power in credit markets toward debtors and away from creditors, mapping relatively cleanly as a shift toward the poor from the wealthy. It is therefore cheap credit in the context of spectacular imbalances of economic power (that shape policy at every level) that has helped accelerate housing price inflation and encumbered access to shelter—something that by all reasonable accounts should be a human right—for many working and low-income people.

The housing crisis is just as much or more so about weak rent control, exclusionary zoning in low-density cities, preferential tax treatment of capital gains (especially capital gains from the sale of principal residences) and low property taxes as it is about loose monetary policy. It is no surprise that Vancouver, with some of the lowest carrying costs of real estate (primarily low property taxes) of any major Canadian city, has experienced the deepest crisis.

While Vancouver and Toronto, as global cities, were the first to catch the bug of extreme housing speculation, the malady is now spreading to smaller cities and towns. In British Columbia alone it is not only Victoria and Kelowna feeling the heat, but even places like Nelson or the Gulf Islands. The notable exception among Canada’s major cities is Montreal, which has a more robust provincial welfare state, much stronger tenant protections and, partly as a result, lower rates of home ownership.

Developers were only too happy to keep building safety deposit boxes in the sky, helping domestic and foreign capital—rather than people—find a home.

Today, one oil boom-and-bust cycle and a couple years of steady growth later, Canadian monetary policy is tightening again, partly driven by housing market conditions. Despite still moderate wage growth and inflation largely within the Bank of Canada’s target band, Governor Poloz has justified recent interest rate increases in part as a means to cool the housing market. At the same time, Prime Minister Trudeau has made much fanfare of getting Ottawa back into housing, which the government now claims to be a human right. (The UN special rapporteur on the right to housing has questioned whether this implies something legally enforceable or is simply window-dressing.)

The Liberals’ National Housing Strategy, unveiled in 2017, promises a $40 billion boost to various housing programs over 10 years, focusing primarily on the most vulnerable. This is a welcome change in tone from government. Unfortunately, the vast majority of these funds are back-loaded until after the next federal election in 2019, and only $15 billion worth is new money.

In addition, the focus on only housing the vulnerable assumes the market works fine for everyone else. Indeed, much of the new housing money takes the form of various rent and private development subsidies that will not shift the fundamentals of private sector-led, investment-geared housing provision. Without a more concerted effort that looks at all the factors behind our long housing boom and affordability crisis, current plans leave much to be desired.

Housing policy alternatives

The neoliberal state we’ve inherited prides itself on not interfering with or, god forbid, regulating markets and financial flows except when inaction might be systemically destabilizing. Unfortunately for the government, our housing sector needs patching up—even if it means breaking out the red tape.

The crisis in our cities is so deep and increasingly widespread that far-reaching and systemic change is needed. And really, whether we like it or not, the housing market is already highly regulated: zoning and land use regulations, mortgage rules for buyers, property taxation and pension design all impact what gets supplied and what is demanded. The question is not whether to “interfere” in the fundamental workings of the housing market, but how and in whose interest.

The question is not whether to “interfere” in the fundamental workings of the housing market, but how and in whose interest.

Both Ontario and British Columbia have instituted foreign buyers taxes. BC has also implemented a mildly progressive property tax on homes valued over $3 million and increased property transfer tax rates. Vancouver has an empty homes tax starting this year. These measures, which are welcome and contributing to cooling the two most haywire housing markets (Vancouver and Toronto) in terms of both sales and price growth, are nonetheless insufficient to the scale of Canada’s post-crisis housing affordability crisis.

Luckily, the alternative policy toolbox is full for those willing to make use of it. Here are some of the sharper implements:

- The direct provision of non-market housing. The public sector should be an aggressive “builder of first resort” that embarks on a massive build-out of high-quality, democratic, non-market housing that the poor, working and middle classes can afford. Direct publicly-provided housing, private non-profit housing, co-ops and community land trusts are all good options. Not only would a rapid build-out eliminate some of the current stigma around social housing, it would directly challenge both the primacy of the market and the prices it currently sets. And it would pay for itself in the long run courtesy of the joint magic of state-backed credit, existing public urban land, and cross-subsidization.

- Stronger tenant protections and rent controls. These measures help people stay in their homes, reduce potential future income streams from land and bring tenancy closer to ownership in terms of stability, security and control.

- An end to exclusive zoning in cities. We can carefully dismantle the system of exclusion that maintains a false scarcity of land and keeps significant portions of our cities off limits to renters and workers. At the same time, we should introduce measures to capture any increases in land values to incumbent owners and redirect that money to the public good.

- Reform of the tax system. Several tax changes would make housing less attractive as an investment relative to other assets and generally increase carrying costs. These include progressive and overall higher property taxes geared toward the taxation of land value at the local level, taxes on capital gains from short-term speculation at the provincial level, and an end to preferential treatment of capital gains at the federal level.

- More generous public pensions. Less pressure on housing as a retirement asset would bring the value of homes and land more in line with their role as places to live.

With rising public anger about housing and rent costs, there might still be a window to use some combination of these tools to end our affordability crisis. As a bonus, meaningful housing reform would ensure that our next economic crisis doesn’t start among the cranes dotting the Vancouver and Toronto skylines.

—

This piece originally appeared in an issue of The Monitor.

Topics: Economy, Features, Housing & homelessness, Poverty, inequality & welfare